While it was never likely to contain too many surprises, this week's much-anticipated Jackson Hole speech from Fed Chair Powell served as an important reminder as to why rates have risen so sharply in August.

The Fed has 8 scheduled policy meetings per year. At the conclusion of those meetings, the Fed releases an official statement which includes any potential changes in the Fed Funds Rate.

The Fed Funds Rate is quite different from mortgage rates, but the things that lead the Fed to adjust its rate hike pace often have an impact on longer-term rates like mortgages and 10yr Treasury yields.

All that to say, there was no official policy statement from the Fed this week and no change to the Fed Funds Rate. Markets were nonetheless eager to check in with Fed Chair Powell and were forced to rely on a brief speech delivered at the Fed's annual Jackson Hole Economic Symposium, or simply "Jackson Hole" to market watchers.

Jackson Hole has been responsible for helping to telegraph a few important shifts in Fed policy over the years. As such, it always garners a bit of speculation as a potential flashpoint for the market, even if the big reactions have been more scarce over the years.

This year was perhaps more deserving of some anxiety considering the Fed's policy path as communicated by Powell in late July and multiple Fed members in the subsequent weeks. In short, the Fed Funds Rate has risen quickly enough that policymakers can BEGIN to consider slowing the pace of rate hikes.

The promise of that policy shift--highly conditional though it may have been--coincided with several downbeat economic reports in late July. The result was July standing as one of the best months for downward movement in mortgage rates in decades. And the market has been pushing back against that exuberance ever since.

Why?

To reiterate, the Fed's late-July message was highly conditional. The slightly friendlier inflation data would need to continue in the same vein for months to build a disinflationary case (inflation is a key reason rates have been as high as they are) and a handful of weak economic reports didn't mean anything conclusive unless they too were joined by subsequent months of deterioration (weaker economic data tends to coincide with lower rates).

To make matters worse, economic data began to improve in August--in some cases substantially. Then speculation increased that July's inflation news was more of a one-off due to a big correction in fuel prices. Last but not least, a slew of other Fed speakers was saying essentially all of these same things over the past few weeks. One of the most sobering parts of the thesis was the need to do damage to the economy (by continuing to hike rates) in order to achieve inflation goals.

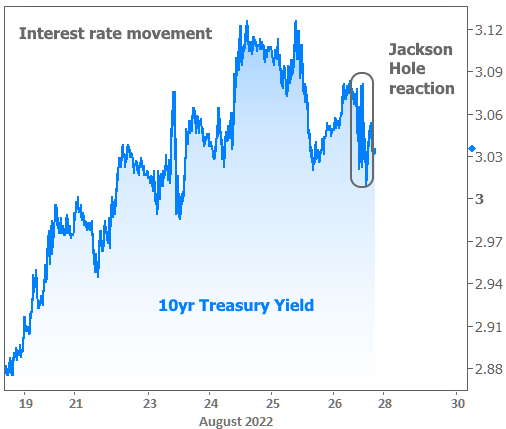

Thus it came to be that the market was positioned at the highest rates in more than a month before Friday's speech from Powell. When Powell bluntly reiterated everything we already knew, there wasn't much for the bond market to do. While that was a good thing in terms of avoiding additional rate spikes, it also meant there was no compelling case for rates to drop quickly. The following chart shows the range-bound indecision in 10yr Treasury yields after having risen throughout the week in advance of Powell's speech.

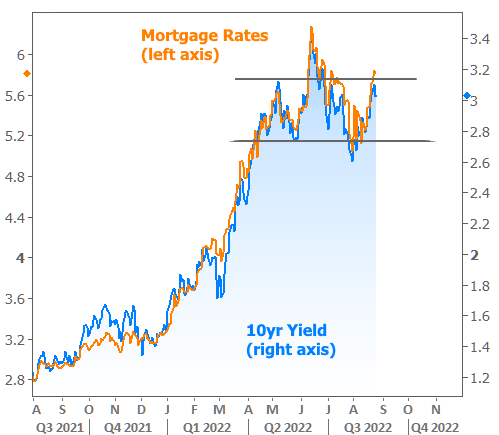

While the 10yr yield doesn't directly dictate mortgage rates, the two are highly correlated most of the time.

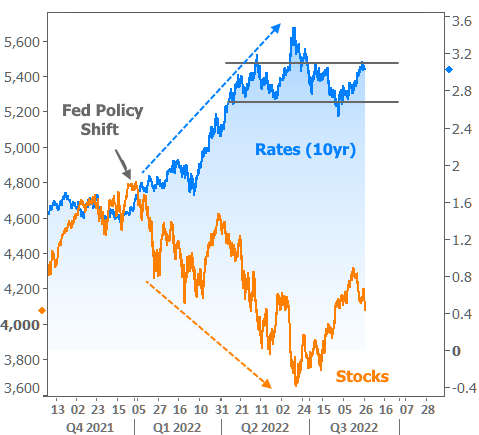

There is a bit of a counterargument to the notion that the market was fully prepared for Fed Chair Powell's direct tone. It comes courtesy of the reaction in stocks. But before we examine that in detail, let's take a moment to remember that friendly Fed policies are like proverbial rising tides that lift all boats. They help both stocks and bonds. Conversely, when the Fed shifts toward tighter policy, stocks and bonds often lose ground together. That's basically 2022 in a nutshell: a big, unfriendly shift from the Fed followed by heavy selling on both sides of the market.

With that in mind, Friday's stock market reaction to Powell suggests stocks were not nearly as well positioned as bonds/rates. In fact, stocks lost so much ground that bonds/rates may have had a bit of additional benefit from investors fleeing the stock market to seek safer havens. In other words, rates might have risen more noticeably after Powell's speech were it not for the stock market taking the news so hard.

At the end of the day, the rate market is probably right about where it should be: not at the absolute highs of 2022, but not taking too much of a lead-off back down to lower levels. In order for a sustained drop to make sense, we need several more friendly inflation readings and, unfortunately, to see the negative impacts on the economy that the Fed is expecting.

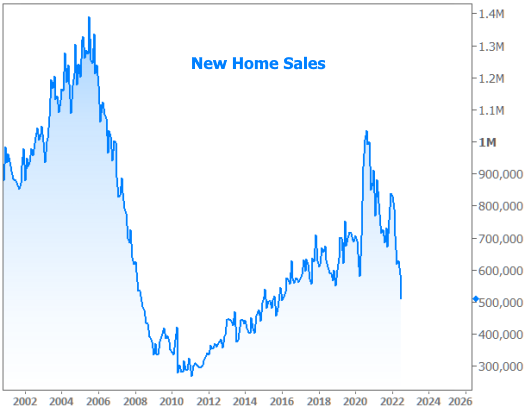

At least one sector of the economy can already claim to be experiencing quite a bit of drama thanks to the shift in rates. If you're anywhere close to the housing market, you already know. This week brought more of the same in that regard with a big drop in New Home Sales.

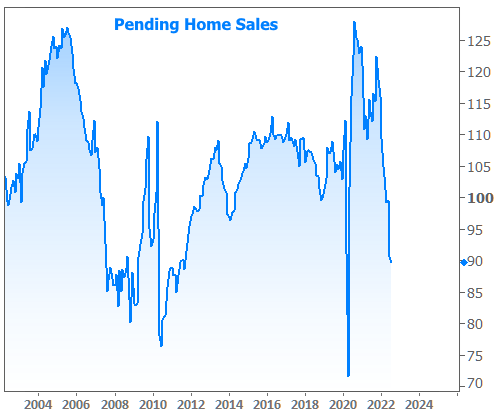

Pending Home Sales also declined, but at a far slower pace in this week's data (which covered the month of July).

The chart above doesn't look great, but keep in mind that July only accounted for a 1% decline versus June whereas June dropped almost 9% vs May. This deceleration prompted a hopeful comment from NAR's chief economist Lawrence Yun, who said, "in terms of the current housing cycle, we may be at or close to the bottom in contract signings."

Looking ahead

Next week could be critically important in shaping the rate trend because it brings several economic reports that have recently had a big impact on rate momentum. Chief among these is Friday's jobs report, which is expected to show a major deceleration in jobs growth from July's 528k to 285k for August.

We'll also get June's FHFA Home Price Index. While that's not a big market mover, it's part of a larger data set that helps determine conforming loan limits. June marks the end of Q2 and will round out 3 of the 4 quarters that feed the conforming loan limit equation. The equation becomes complete in late November when Q3 home prices are released.