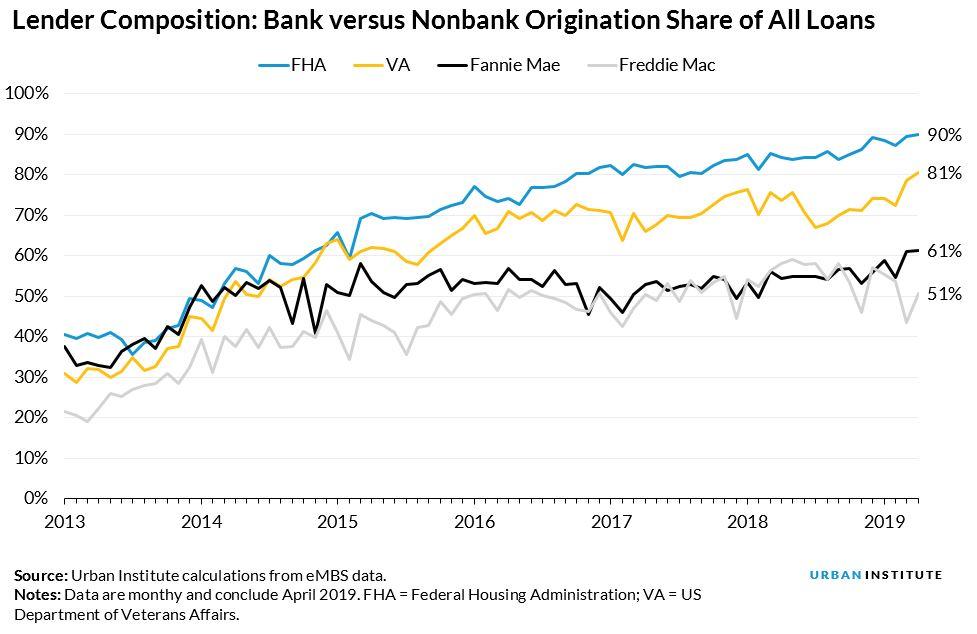

After the housing crisis and faced with a flood of insurance claims, FHA and the Department of Justice responded with enforcement efforts against lenders that had made underwriting mistakes, levying large fines, requiring more indemnification, and bringing claims of fraud under the False Claims Act. Urban Institute (UI) analysts Jim Parrott and Laurie Goodman write that this generated confusion among lenders, first because they hadn't faced such enforcement actions in the past and second because the rules weren't being applied consistently or predictably. Many, especially the large, well-capitalized ones, cut back, sometimes dramatically, on FHA lending and eventually newer, often less capitalized lenders filled the gap, leading to a shift in counterparty mix.

This makes the FHA market less durable. Some of the less robust lenders are likely to fail or pull out of lending should defaults start to rise, making FHA less able to fulfill its countercyclical role as well as it did in the last crisis. It also creates significant counterparty risk to Finnie Mae which might have to step in to manage the servicing obligations of lenders who don't survive a downturn.

In May FHA announced some proposed changes to its lender rules in an attempt the make it easier to do business with FHA single-family operations. These changes, briefly, include the following.

- Revisions to the Addendum to the Uniform Residential Loan Application form to make it more logical, easier to read, and remove requests for information collected elsewhere.

- Changes to annual lender certifications to better align them with National Housing Act standards while still holding lenders accountable for compliance with HUD eligibility requirements.

- Changes to the Defect Taxonomy Version 2 to include updated Severity Tier definitions; potential Remedies that align each Severity Tier; revised Sources and Causes in certain Defect Areas; new Defect Areas for Servicing loan reviews; and, HUD policy references.

This is just the latest of FHA's attempts to draw more substantial lenders back into the fold. The third of the changes above is intended to clarify to what lenders are attesting when they submit a claim to for FHA insurance by creating a taxonomy of remedies that reflects the relative significance of different kinds of lender mistakes. The authors say this is the right approach - lenders need both a clarification of what the rules are and how they will be enforced. The lack of distinction regarding the treatment of truly consequential and minor mistakes has been one of the key reasons keeping lenders at bay. "Since it is difficult to avoid making smaller mistakes in processing loan files that often run hundreds of pages long, many lenders have chosen to control their risk by reducing the probability that they have to file an insurance claim with FHA in the first place. They do this by refusing to offer FHA loans to many of the higher risk borrowers it is FHA's mission to serve," Goodman and Parrott say.

When submitting an insurance claim a lender must certify that it has followed the underwriting rules at loan level. The changes to the Defect Taxonomy attempt to clarify how FHA will handle failure to comply with loan-level certification rules by ranking categories of mistake by severity. This is the right approach, the authors say, as it clarifies both what lenders are certifying and what FHA will do if they make a mistake. "The problem is that it doesn't address what DOJ will do if a lender makes a mistake, thus leaving unaddressed the biggest, most uncertain source of liability of all: the False Claims Act."

In fact, they say the clarification of the lender's exposure to FHA enforcement seems to expand exposure to enforcement by DOJ, clarifying the need to certify compliance then narrowing the lender's exposure to FHA enforcement through the taxonomy. But DOJ brings an action for a violation of the False Claims Act because a certification of information later proves untrue, not because of mistakes that happen to fall into certain categories in the taxonomy. "By clarifying that lenders are certifying to perfect compliance with FHA's thousands of rules, FHA is clarifying that lenders are exposed to False Claims Act liability for any and all mistakes, irrespective of substance, size, intent or where it falls in the taxonomy."

The authors say they doubt any lender avoiding the FHA over enforcement uncertainty would return in response to the changes. FHA needs to narrow either the range of what a lender must certify or the kind of mistakes that can give rise to liability under the False Claims Act. For instance, under the proposed Loan Level Certification the lender must now certify that "All conditions of approval have been satisfied." Instead, FHA could require certification that "to the best of mortgagee's knowledge, all conditions of approval have been satisfied in all material respects." This would remove the threat of treble damages for small mistakes of which the lender was not aware and that has no bearing on the risks to FHA.

Such narrowing would give lenders a reasonable chance to avoid mistaken attestations, but the authors say the changes needed are numerous and only one poorly placed ambiguity would leave the status unchanged. "Given the now long record of differing interpretations that lenders, FHA and DOJ all bring to key passages, there is reason to be skeptical that any revisions would provide adequate clarity."

They suggest instead tying False Claims Act liability to the taxonomy. It would require joint action from FHA and DOJ but stating explicitly in the taxonomy that a claim under the False Claims Act is a possible remedy for specific categories of more severe mistakes and only these categories would finally create a more coherent, integrated, and comprehensive enforcement regime. This could give lenders an incentive to improve their quality control, rather than abandoning riskier borrowers, the target FHA is designed to serve.

Goodman and Parrott conclude, "The bottom line is that if the administration wants to attract back into the FHA market those lenders scared off by uncertainty over how FHA's rules are enforced, it will have to provide some certainty over when and how the False Claims Act will be used. Either of the approaches we suggest could made to work, and there are no doubt others. But any approach that leaves out this critical piece of lender liability will inevitably fall short."