Sean Becketti, Freddie Mac's Chief Economist said that there is a tendency for housing and mortgage markets to focus on high profile but transitory events - for example the weekly reports on interest rates - while the factors that will actually determine the future of housing evolve so slowly we tend to overlook them.

He points to three long-standing trends: increasing income inequality, the increasing role of land costs in housing prices, and increasing land use restrictions. These, he writes in Freddie Mac's monthly Insights, will shape the future of housing by permanently shifting both the demand for and supply of housing.

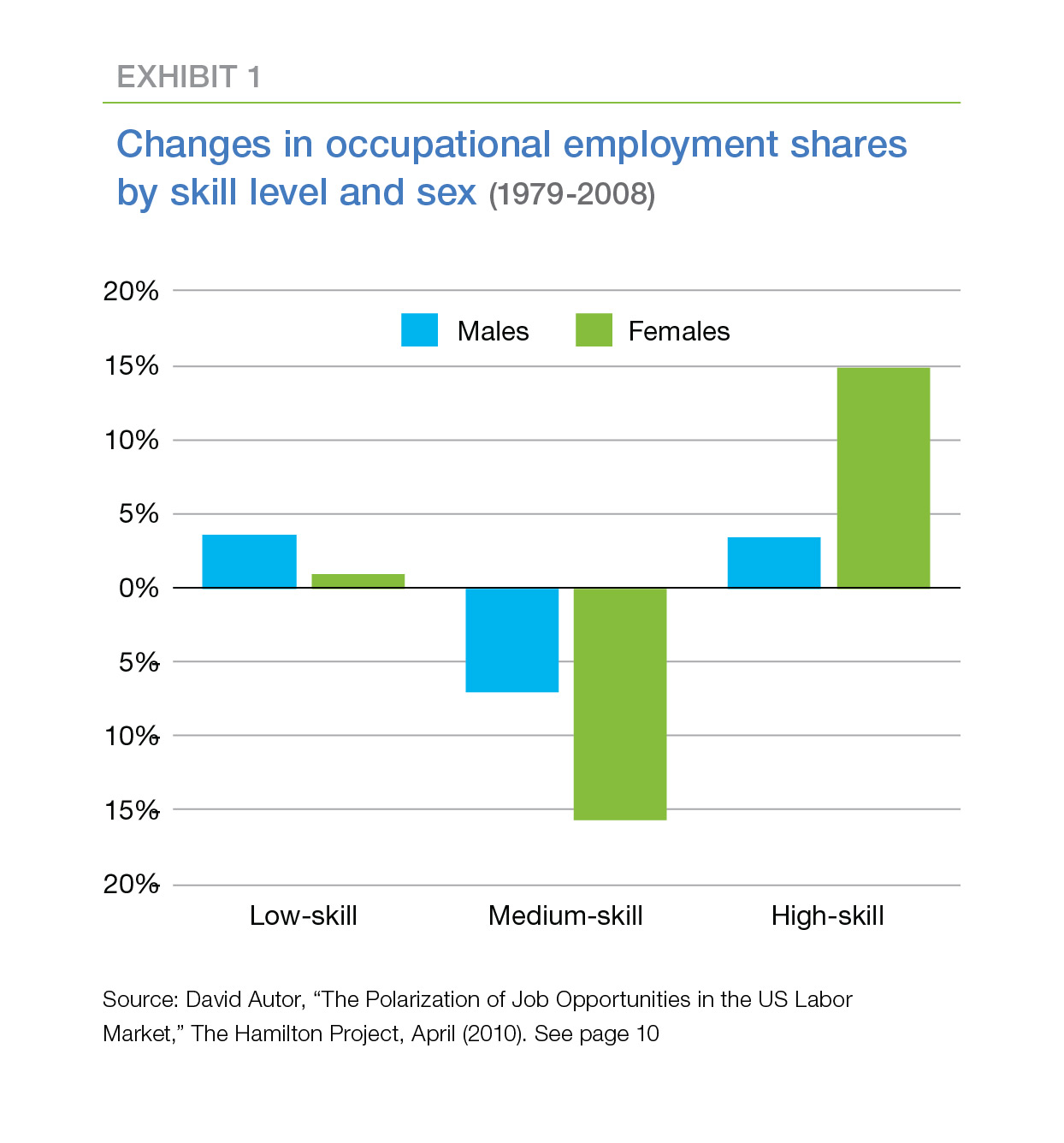

Increasing income inequality is the first and possibly most important trend, but not the growing gap between the richest and the rest. The high pay and lavish lifestyles of the "1 percent" makes news but what really matters are the shifts in the relative fortunes of low, middle, and high-skilled workers. Those began decades ago and continue today. The fortunes of these workers are being driven by the changing job landscape in which job opportunities are polarized.

As shown in Exhibit 1, demand has increased for both high-skilled, high-wage workers and low-skilled, low-wage workers while demand for middle-skill jobs has decreased, helping to "hollow-out" the middle class. Technology has eliminated white-collar clerical, blue-collar production and craft, and related jobs such as the 7,000 accounting and invoicing positions Walmart eliminated in August.

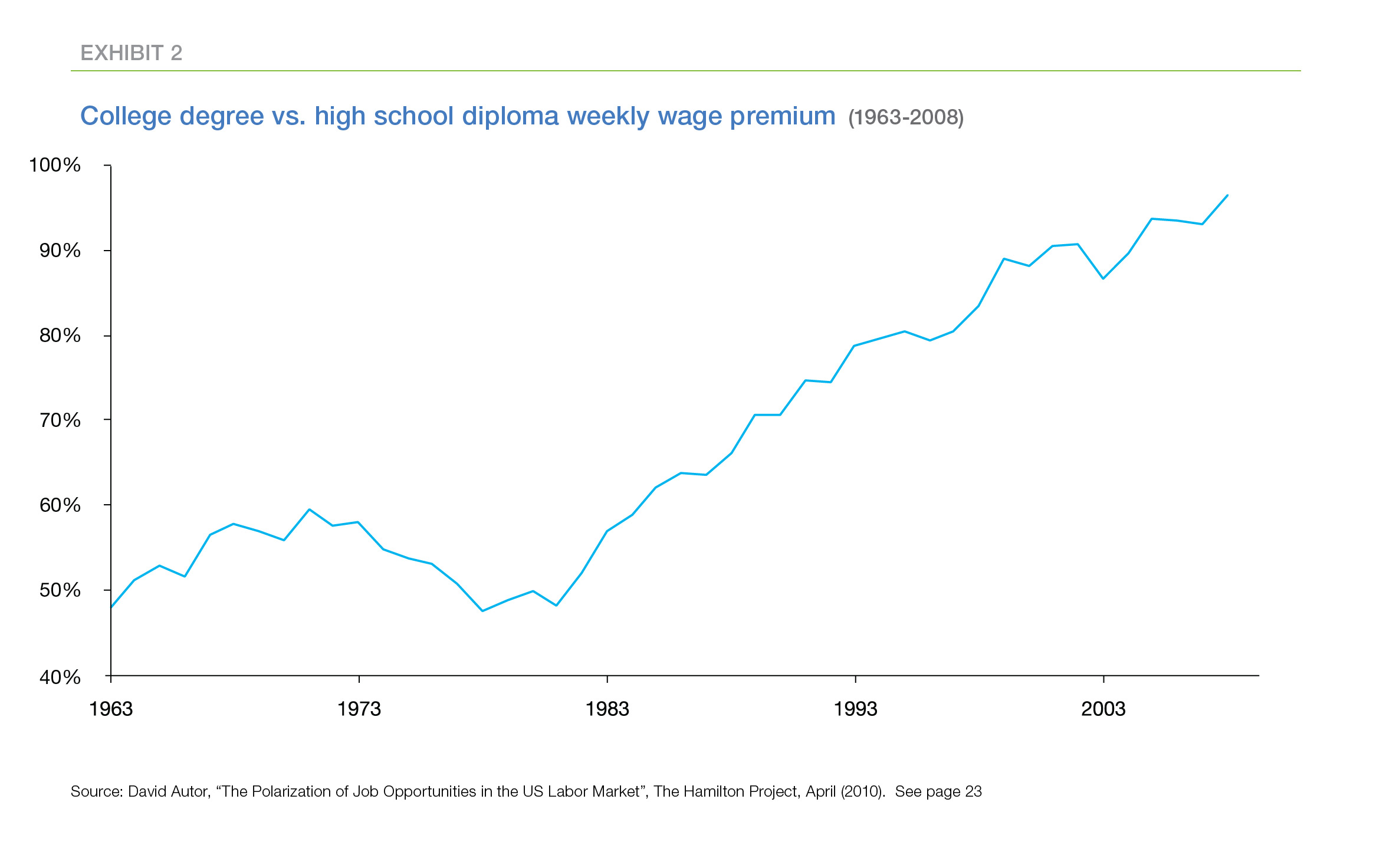

The real earnings of college-educated workers have increased while the real earnings of workers without college educations have fallen, magnifying the earnings gap between high- and low-skilled workers. Since the mid-1970s, increasing demand for skilled workers has outpaced educational attainment adding to wage inequality. For example, in 1980, workers with four-year college degrees earned 50 percent more per hour than high school graduates; today the difference is 95 percent.

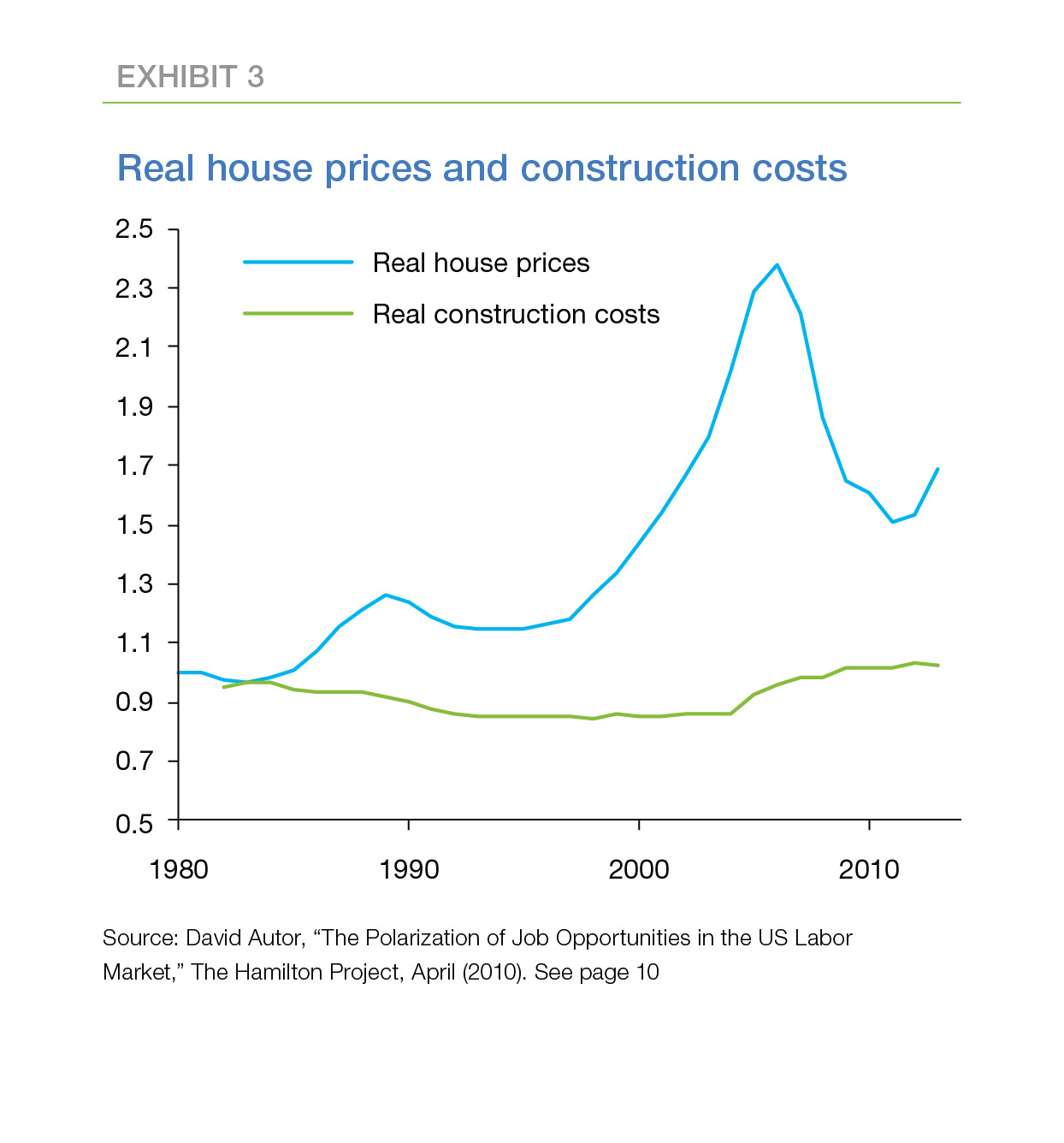

The second stealthy trend is the growing share of home building costs attributable to land. The country still has vast open stretches but buildable land within a reasonable distance of population and employment centers is increasingly scarce. In some places, San Francisco for example, about the only way to build a new house is to knock down an old one which doesn't grow the supply. Other locations may be surrounded with undeveloped or lightly developed land but often at a distance from core cities. This means building in areas with fewer existing amenities and higher commuting costs to jobs and services.

At the same time, real construction costs have increased slowly, giving the land component an increasing cost share. From 1996 to the peak of the mid-2000s housing boom, real house prices more than doubled while real construction costs increased only 12 percent. Even today, after real house prices have retreated from their peak and real construction costs have increased another 12 percent, the share of land costs is much higher than in the mid-1990s.

A third and related trend is increasing land use restrictions. Becketti points to research by Peter Ganong and Daniel Shoag that shows how migration narrowed the income gap among states. For a century residents of poorer states moved to take advantage of higher wages available in richer states. This restrained wage growth in those states while scarcity of labor boosted them in poorer ones.

Over the past three decades, however, this rate of this convergence has slowed and the authors blame increasingly-strict land use regulations in the richer states. They caused higher housing costs, making migration more difficult for low skilled workers while higher skilled workers could still afford them. The increase in hourly wage inequality from 1980 to 2010 might have been 10 percent smaller if the narrowing of state to state income gaps had maintained its earlier pace.

All three trends impact either the supply or the demand sides of housing. The change in income distribution shifts the demand both for homeownership and for different types of housing. The rising share of land costs impacts supply, driving home prices higher, and land use restrictions limit the supply of more-affordable housing in richer states. Becketti says this can lead to long term impacts including;

- A potential boost to the homeownership rate;

- Increasing housing inequality;

- Growing house price volatility;

- The return of homeownership as an effective means of wealth creation;

- Possible shifts in the FHA/VA, GSE, and private sector shares of the mortgage market.

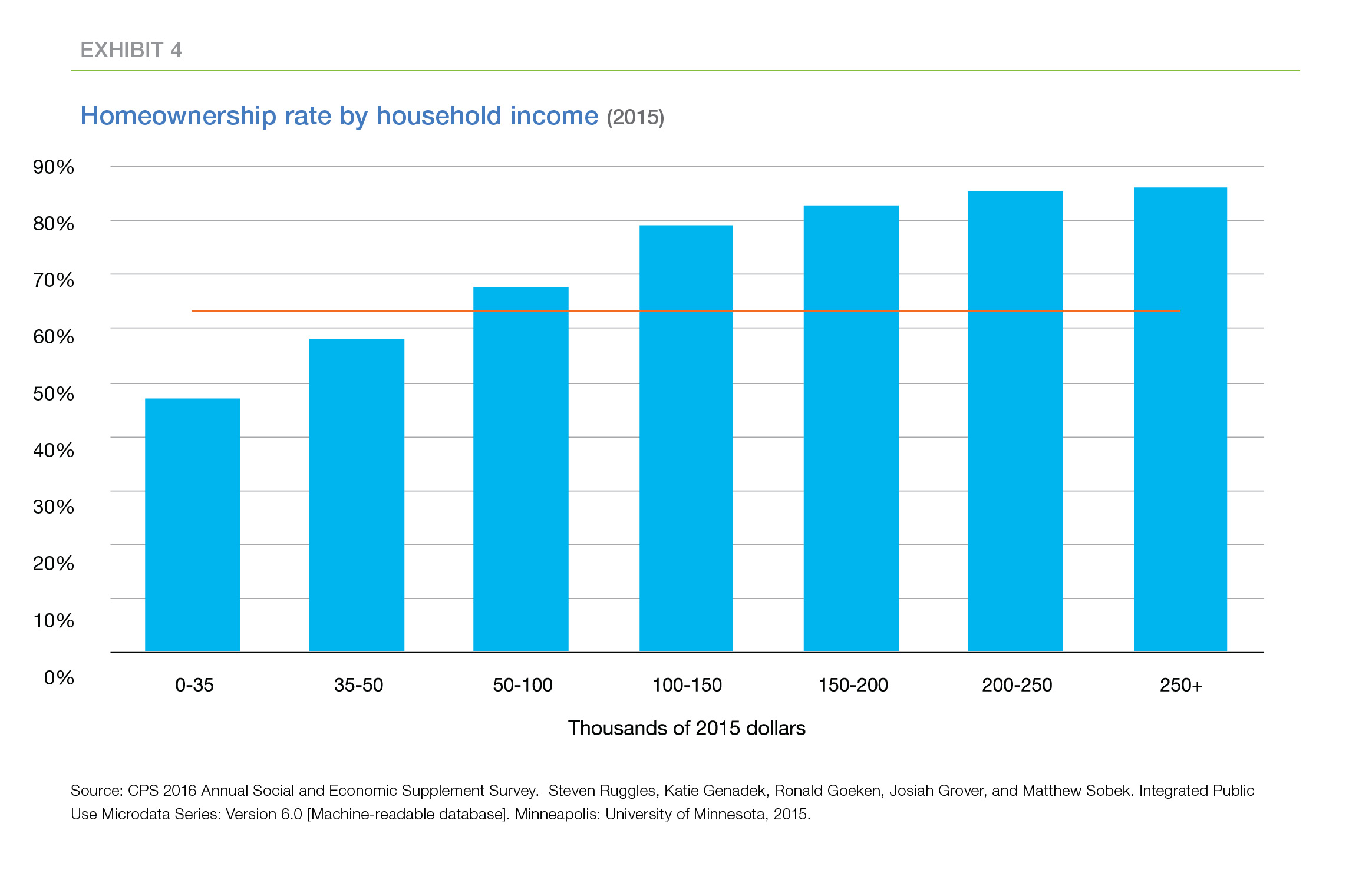

Since higher-income households have higher homeownership rates, any boost in homeownership rates depends on the way that households are pushed out of the middle of the income distribution and toward the extremes. We see in Exhibit 4 that homeownership rates increased sharply in 2015 in households with incomes up to $150,000, then more slowly at higher levels. The red line marks the most recent rate, 63.5 percent in the third quarter of 2016.

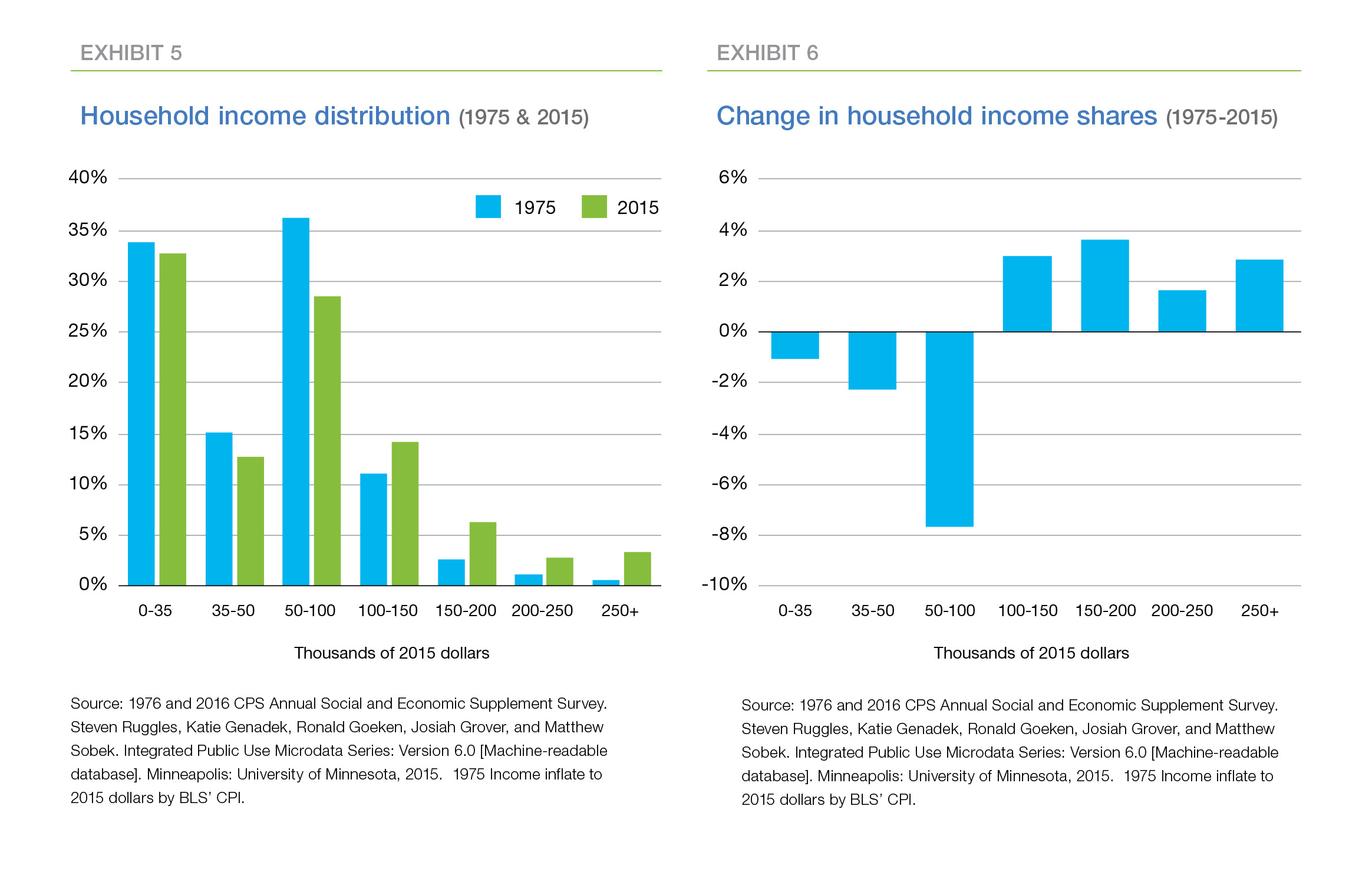

The trend toward the polarization of jobs (and income) has been in place since the mid-1970s so the shifts since then may indicate the future pattern of income distribution. Exhibit 5 compares the income distributions in 1975 and 2015. Exhibit 6 displays the changes in income shares.

Becketti says, given the increased demand for both low and high skill jobs at the expense of the middle, one might expect Exhibit 6 would instead display a U-shaped distribution, with fewer middle class/income households. Instead we see a shrinking share of all income categories below $100,000 while the share of all higher income categories grew. If we classify as middle-class those households with incomes between two-thirds and two times the median household income, roughly $35,000 to $100,000, the share of such households fell from 51 percent to 41 percent between 1975 and 2015. At the same time the share of upper-income households rose from 15 percent to 26 percent and the share of lower-income households fell 1 percentage point, to 33 percent.

This unexpected pattern of Exhibit 6 most likely reflects the challenges of linking skill levels to household income as skill levels are scattered throughout the income tiers. The distribution of real incomes has improved for all skill groups over the last 40 years, thus subtracting population share from the lowest income group. The number of wage earners in each household may have also grown, increasing household income while not representing individual wage growth.

In any event, income distribution has shifted over the last four decades in a way that favors homeownership. If we assume that this pattern continues over the next forty years, we will see a 2-point drop in the share of $35,000-to-$50,000 households; 8 points in the $50,000-to-$100,000 category and so on, and that the relationship between household income and homeownership is unchanged. Under these assumptions, the national homeownership rate will increase three percentage points, from 63 percent in 2016 to 66 percent in 2056.

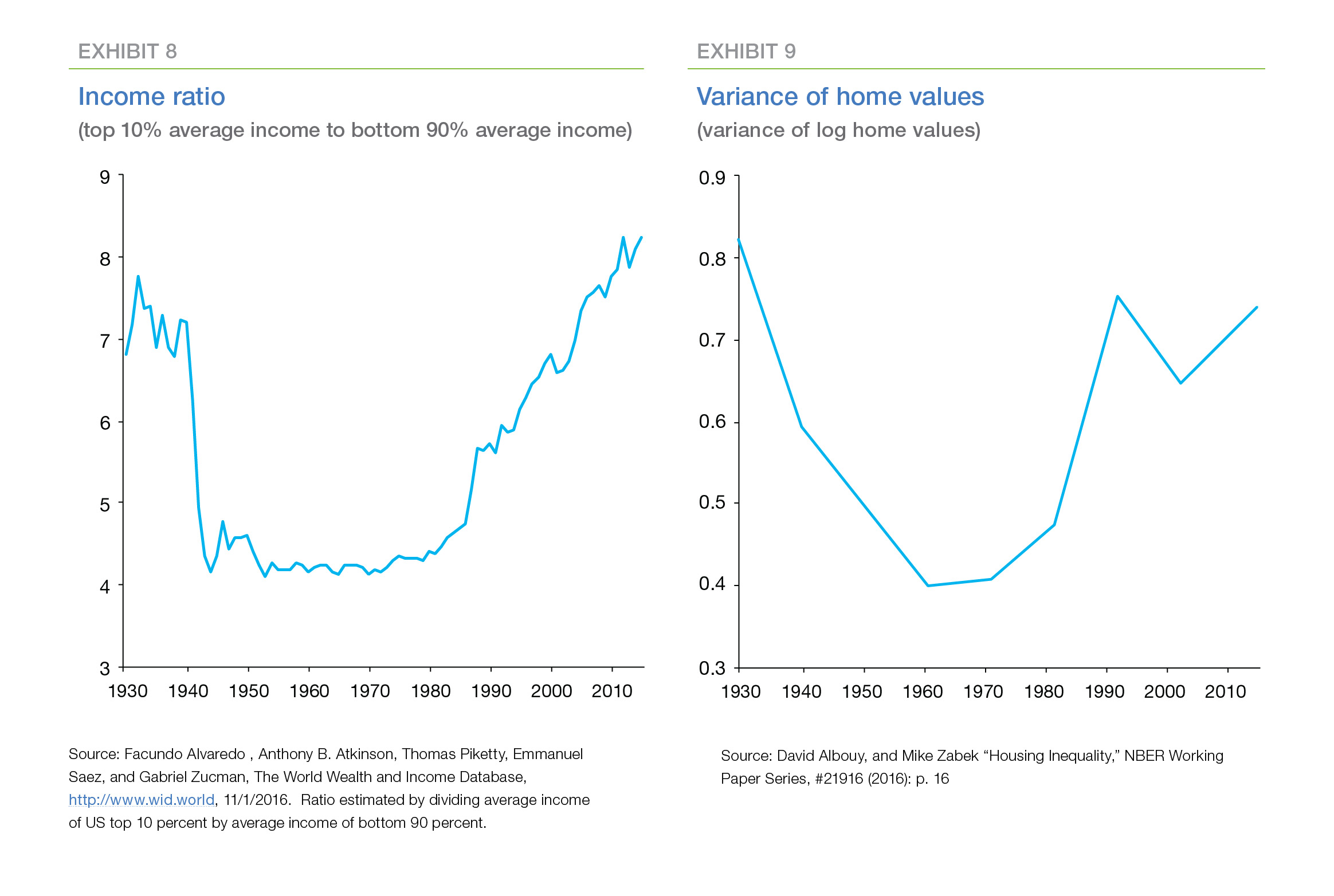

As one might expect, the increase in income inequality over the last 40 years has been mirrored by an increase in housing inequality, but measuring it is not simple. There are many aspect of the quality of a housing unit including size, neighborhood amenities, and distance to economic centers. Albouy and Zabek calculated instead estimates of the consumption value of housing services, that is, an imputed rent, and found that housing inequality decreased from 1930 to 1970 as the rate of homeownership increased by almost a third. However, from 1970 to 2012, the trend reversed and housing inequality increased, mimicking the pattern of income inequality. They also found that inequality is greater within cities than between cities. Since construction costs within cities do not vary much, they conclude that inequality in land values and variations in land use restrictions within cities are responsible for much of the within-city housing inequality.

Scarcity of building land also appears to foster house price volatility and this is exacerbated by land use restrictions. Both make it difficult for the supply of housing to readily expand in response to demand.

The nationwide collapse of house prices in the mid-2000s prompted reconsideration of the importance of homeownership as a factor in middle class wealth creation. In fact, many families in underserved groups lost both their homes and their hard-earned down payments in the housing crisis. Becketti says all three of his trends suggest that homeownership in richer states and desirable metros will again be an effective in creating wealth as the polarization of jobs increases the share of upper income households which in turn is increases the demand for more-expensive homes. The long-term return on housing investment in richer areas will be especially high, but smaller in poorer states with more available land and fewer zoning restrictions.

A simple way of looking at the impact these trends will have on the mortgage market is by dividing it into three overlapping sectors. The FHA and the VA focus on first-time home buyers, lower-income borrowers, and credit-challenged borrowers. The GSEs, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, cover a wider range, providing the bulk of funding to middle-income borrowers while also providing significant funding for other income groups. Banks provide jumbo loans to more affluent borrowers.

Exhibit 11 shows that most of the FHA/VA borrowers are lower-income while virtually all jumbo mortgages are taken out by upper income borrowers. The GSEs provide a significant share of loans to borrowers in all three income classes.

The shift in household income distribution discussed above is also likely to shift the shares of mortgage finance supplied by these three sources over the next few decades. The jumbo share will almost certainly increase along with the growing share of upper-income households. The FHA/VA share may plateau or even shrink if the share of lower-income households continues to decline. The impact on the GSEs is difficult to predict, since the GSEs provide mortgage finance across the entire income distribution. And, of course, the influence of future legislative changes in the mortgage finance system could outweigh the impact of the trends in the household income distribution.

Becketti concludes that increasing income inequality, the rising share of land costs and land use restrictions have crept forward and have escaped the spotlight shown on other recent events such as the boom and bust of the 2000s. Nonetheless, these three trends will shape the future of housing long after the influence of more recent events plays out.