The debate over whether the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act was desperately needed or a pox upon the land survives even as its fifth birthday passed in late July and is likely to become more heated as the 2016 election nears. The structure and even the existence of its most controversial outcome, creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), is constantly threatened by both legislation and court action.

CoreLogic's current edition of MarketPulse, its on-line magazine, attempts to take a measured and objective look at the Dodd-Frank Act "The Lingering and Lasting Effects". Policy research and strategy analyst Stuart Quinn says of the act, "The half-decade (of the Act) has further amplified its divisiveness, with legislators from both sides of the House hitting the speaking circuits to either magnify the blemishes or, tout the progress."

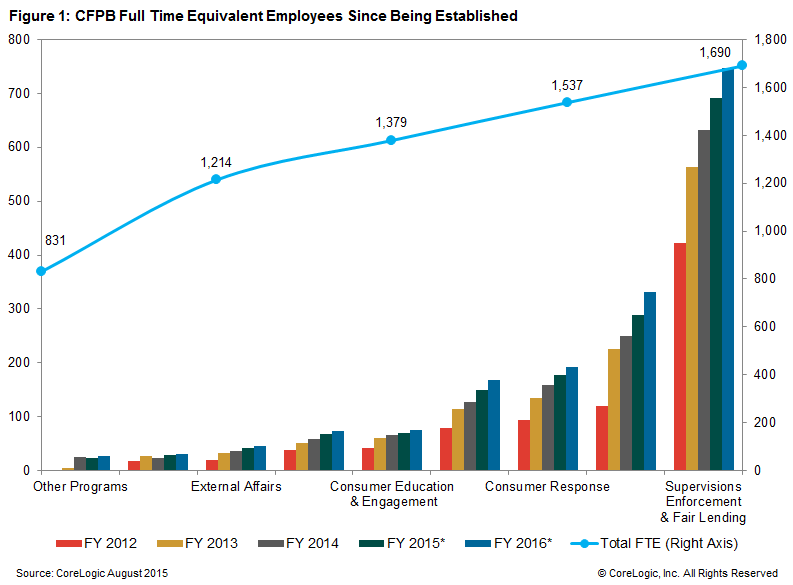

In addition to the CFPB, other agencies established by Dodd-Frank include the first Federal Insurance Office, the Office of Financial Research at Treasury, Office of Housing Counselors at the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the Office of Credit Ratings. CFPB operated for two years without a confirmed director but grew quickly, transferring both employees and functions from the Federal Reserve and several federal agencies but remains, Quinn says, rather lean by federal standards with a current roster of 1,537 employees. The staff tilts heavily toward enforcement with a 10 to 1 ratio of Supervision, Enforcement and Fair Lending staff to Consumer Education and Engagement employees.

Dodd-Frank also established a Civil Penalty Fund designed to compensate consumers who suffer from a violation of a federal consumer protection law. To date the fund has collected approximately $207 million from more than 45 different entities or persons found to have broken these laws.

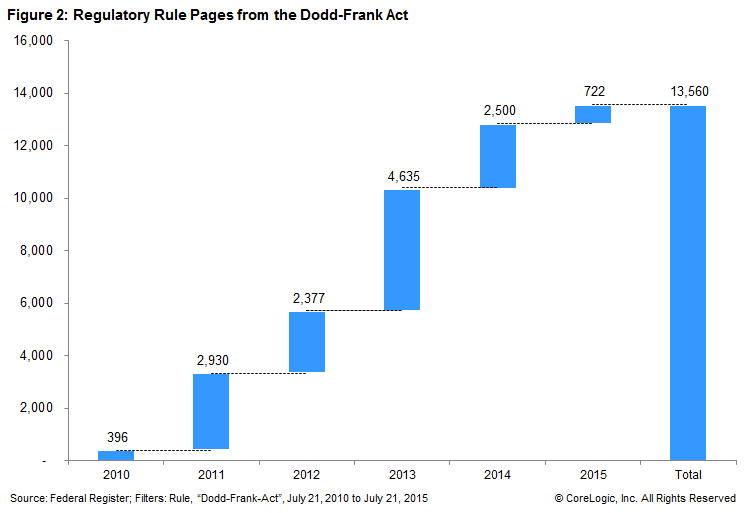

According to the Federal Register over 13,000 pages of published rules have come out of Dodd Frank, 2,000 of which had come from CFPB by 2013. Other agencies publishing large volumes of rules are the Commodities Future Trading Commission (801) and the Securities and Exchange Commission (646). The most notable of the rules completed by CFPB by the end of 2013 include Qualified Mortgage/Ability to Repay (QM/ATR), Mortgage Servicing Rules, and the Integrated Mortgage Disclosures (TRID).

Quinn notes that there was significant concern within the housing finance industry about QM/ATP and its impact on future originations. However the exemption established for loans eligible for purchase by the government sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac along with other exceptions for smaller institutions and rural lenders muted at least near-term origination concerns.

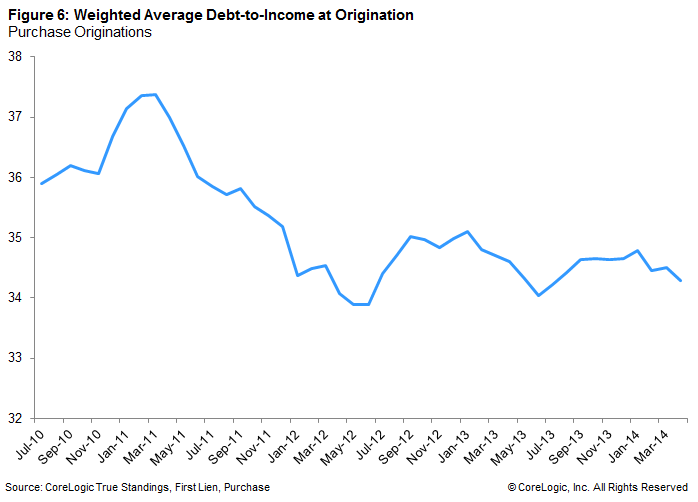

He says Dodd-Frank rules for housing finance seemed to have merely solidified what were already trends in originations. He cites low/no documentation loans which had peaked at 42 percent at the end of 2005 and by the time Dodd-Frank became law five years later their number had tumbled to a 4 percent share of purchase mortgages. Adjustable-rate mortgages, not banned by the act but treated differently than fixed-rate loans under QM rules, had also largely disappeared comprising only 7 percent of purchase originations. The one origination trend which Quinn said did pivot was the average debt-to-income (DTI) ratio which, in the month Dodd-Frank was signed peaked at 37 percent.

In April 2011 the Federal Reserve proposed a QM/ATR rule indicating that DTI would be one factor although no specific threshold was given. Since then Quinn says the weighted average back-end DTI of purchase originations has dropped to 33 percent, 10 percentage points below the 43 percent DTI threshold established in the final QM/ATR rule that went into effect in January of last year.

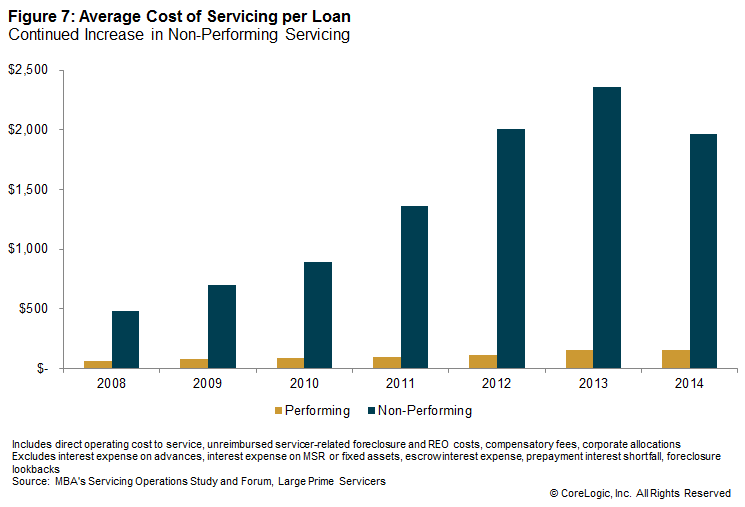

The final mortgage servicing rules promulgated by CFPB had similar provisions to those in previous consent orders and/or the 49-state servicing settlement. Since then the cost of servicing, especially of non-performing loans, has continued its upward trajectory and foreclosure timelines in some jurisdictions remain extremely long even as the volume of distressed loans has decreased.

Quinn says the question, five years after Dodd Frank remains whether true national servicing standards have been attained or if they realistically can be and whether an appropriate compensation structure covering both performing and non-performing loans has been reached. There is also Congressional action possible regarding treatment of mortgage servicing rights under new Basel III standards.

Five years out a number of rules authorized or mandated by Dodd-Frank either have not yet been finalized or become effective including TRID and the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act. Other broader reforms including legislation on too-big-to-fail, executive compensation, and the Volker Rule remain outstanding or under debate. Quinn says even as mortgage reforms are being implemented some results are difficult to measure because of the absence of a true private label securitization market, inaction on GSE reform, GSE credit policy changes, and "the pristine quality of originations in the post-Dodd-Frank era."

He concludes, "The dialogue in Washington revolving around the Dodd-Frank Act continues to bubble. How many more rules will the CFPB finalize and what effect will these regulations have on the financial services industry? The next five years will be just as interesting to analyze when it comes time to celebrate the 10-year anniversary of the Dodd-Frank Act."