Could lower energy costs translate into a more lively real estate market? It seems logical - the less consumers must spend to keep their cars moving and their houses warm the more they can save toward or spend on owning a home. CoreLogic Senior Economic Molly Boesel takes a different approach to the question, one revolving around the cost of commuting, in an article in the company's blog Market Pulse.

Boesel says that home heating oil prices in the first week of November were 40 cents lower than they were at the same time in 2013 and that in the four weeks before her article was written the average price of gasoline had fallen by almost 30 cents to just over $3 per gallon, the lowest since the end of December 2010. (After last Friday's energy bloodbath AAA puts the average price at $2.769). However, she sees only gasoline prices as having a direct impact on housing choices.

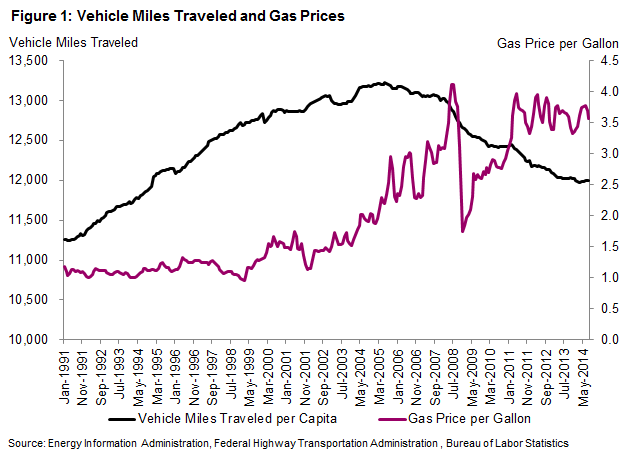

Gas prices remained under $2 per gallon for the first 13 years she tracks in Figure 1 while per capital vehicle miles traveled (VMT) increased steadily. Those miles began to level off as gas prices surpassed $2 and then to decline as they reached $3 per gallon. After that mileage declined steadily even as gas prices bounced around, surpassing $4 on one occasion and falling below $2 on another. VMT in August 2014 were at about the same levels as in 1994. Boesel notes that some of the drop in driving can be attributed to the extreme stress (and probably a drop in commuting due to unemployment) of the financial crisis.

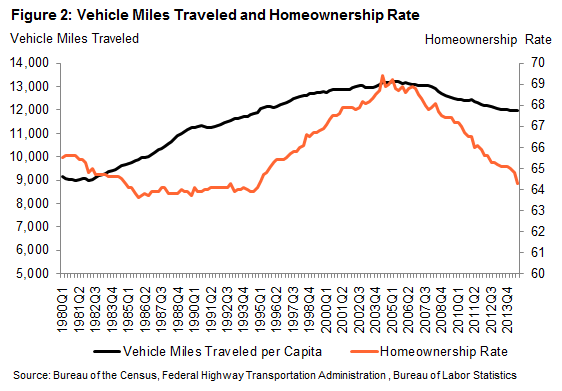

Homeownership rates more or less paralleled VMT between 1994 and 2004. During this period VMT increased by 12 percent and homeownership rose by 5 percentage points. Boesel says that, with gas prices under $2 some of the increase in homeownership occurred as many homebuyers moved further from the urban core to buy larger and more expensive homes. Then in 2005 the trend reversed and homeownership as well as VMT has now fallen back to 1994 levels.

So Boesel asks, if consumers believe the drop in gas prices is here for a while, might it incentivize them to again migrate outside of urban cores? She quotes a paper written in 2012 by Sexton, Wu, and Zilberman which found that low fuel prices helped lead to urban sprawl, pushing the lowest income mortgage borrowers furthest out into the suburbs and where they were the most vulnerable to the energy price spikes of 2008 and later. However, she concludes, "Another major factor that led to that sprawl was an environment of easy credit and low interest rates - and while interest rates today are low, credit is tighter than it was in the mid-2000s, making the decision of whether or not to move far from the urban core a very different calculation."