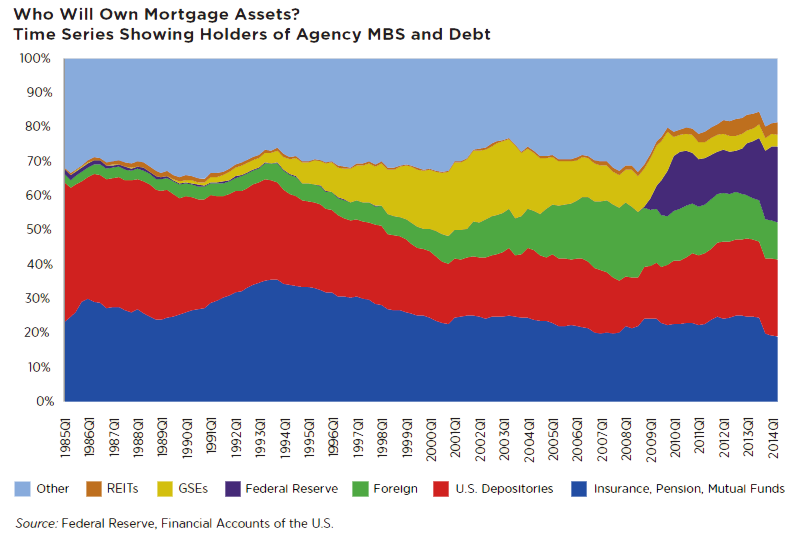

The Federal Reserve has completed its latest round of Quantitative Easing, the government sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae are under orders to continue shrinking their investment portfolios and significant constraints exist to keep private investors from purchasing agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS). So who, the Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA) asks, is going to pick up the slack?

A white paper written by MBA's vice president and senior economist Michael Fratantoni, lays out the conundrum facing the MBS market. Fratantoni says both policy makers and the housing industry have a common interest in bringing private capital into the mortgage markets but the key question is how and in what form that private capital can best reenter the system. MBA has advocated for private capital to have a larger role in covering credit risk within the government guaranteed, conforming portion of the market but we need to consider how to draw it to the interest-rate risk of the conforming market and how to reengage it for lending outside of the government guaranteed system.

For years, the GSEs' ability to issue long-term fixed-rate debt appeared to be a stabilizing factor for the U.S. housing finance system. Long-term, fixed-rate debt issued by the GSEs was a better match for funding long-term fixed-rate MBS than other funding instruments but the GSEs' purchase of fixed-rate MBS with minimal capital turned out instead to be destabilizing because they did not have enough skin-in the game.

The GSE's investment portfolios which once topped more the $1.5 trillion have been reduced under their post-crash agreement with Treasury, to less than $1 trillion. Fratantoni said he is not arguing with that policy choice but those portfolios did historically serve to channel global capital into the U.S. mortgage market absent bearing the uncertain cash flows from directly owning mortgages or MBS. Now it has to be asked how the market can be structured to attract stable private capital over time without GSE investment portfolios playing that role.

Confronting this issue has been delayed, first by the Federal Reserve's purchase of more than $1.7 trillion of agency MBS over a five year period; in many months this accounted for the vast preponderance of issuance. But in October the Fed stopped growing its portfolio although it is likely to continue replenishing it until the first increase in the Fed's target short-term rate. Then, likely at some point in the middle of 2015, this major investor will be leaving the MBS market, according to Fratantoni.

Second, modest supply has required little demand. MBA estimates that origination volume in 2014 will be the lowest in 14 years with correspondingly less MBS issuance. Reduced supply has kept spreads relatively tight, even as the GSEs have been net sellers and the Fed has tapered its purchases.

Third, demand from banks has been relatively strong. Banks have made up the difference in their relatively low loan-deposit ratios by maintaining, even increasing their securities holdings. However Basel II standards have recently led larger banks to favor whole-loan over MBS holdings, increase holdings of jumbo and near-jumbo whole loans, and to preferentially hold Ginnie Mae rather than GSE MBS on their balance sheets.

Fourth, attention has been focused primarily on policy steps to improve the efficiency of the secondary market - i.e. proposals to issue a single GSE security to level the playing field between Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and as a step toward GSE reform. As the market continues to recover however ensuring adequate investment will become more important.

As of June 30 2013 the Federal Reserve estimated there was $13.3 trillion in outstanding mortgage debt, $10 trillion of it residential mortgages. These mortgages were held as assets by a variety of investors; $4 trillion by depositories, $4.8 trillion by the GSEs and $76 billion by individual households. GSE MBS are held by the same types of investors but the Fed's holdings of$1.7 trillion almost match those of the entire banking system. Post crisis MBS holdings have fallen at the GSEs but increased among mutual funds, credit unions, banks, and REITS.

Banks and other depositories have been major holders of mortgages and MBS but adjustable-rate and shorter-term mortgages are better matched to their funding than long-term, fixed-rate mortgages. Consumer preference and Dodd-Frank regulations have made fixed-rate products more common but the Savings and Loan crisis remains a cautionary tale about financing long-term, fixed rate loans with short-term liabilities (i.e. deposits) as in rising rate environments.

The Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBanks) have helped banks support their financing of mortgages and hedge interest rate risk. While banks are potentially a key source of private capital their ability to invest in the mortgage market is being restricted by regulatory and market limitations.

- Basel III and other rules have increased capital requirements;

- FHFA has proposed new limitations on FHLBank membership

- Banks are likely to increase commercial and industrial lending, limiting funds available for mortgages

- As rates rise it is likely that depositors will seek higher yields elsewhere.

- Liquidity coverage ratios (LCR) for larger banks penalize banks holding GSE MBS while favoring Treasury and Ginnie Mae securities.

- The banking system's role as counterparties in the repo market is coming under fire by regulators and there are plans to shrink this market.

A second natural set of investors in mortgages are institutional investors including pension and mutual funds. As of March the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Index had a weight of roughly 31 percent for securitized assets (MBS, ABS and CMBS). Fratantoni says it is reasonable to assume these investors would significantly increase their holdings of mortgage-related assets in the aggregate only if mortgages became a larger share of all fixed income, or if they delivered a better return on risk. Looking at U.S. budget deficit forecasts it looks likely that mortgage assets may be a smaller share of the total than in the past, as Treasury issuance ramps up once again although mortgage asset yields may increase to attract more investment.

Broker-dealers, while not significant long-term mortgage holders, have played an important market liquidity role through their holdings of inventory of various assets, and their ability to intermediate repo funding. Regulatory changes have led many firms to pare their inventories of MBS and regulatory focus on the repo market has also led to uncertainty over the long-term availability of cost-effective repo funding and which firms will provide such capital. Moreover, new rules with respect to margin requirements for essentially all participants add further complexity to this market.

Support for mortgage markets has also come from foreign investors. While the U.S. has large trade deficits it has long run a capital account surplus with the rest of the world - i.e. foreign investors save more in the U.S. than the reverse - and a portion has been directed into the mortgage market with its depth of liquidity and higher yield than Treasury securities. However, post crisis, there has been a notable decline in foreign investors' willingness to hold MBS without an explicit government guarantee. Still there has been a very large increase in funds globally seeking safe, fixed-income investments and there have been repeated "flights to quality" over the past several years when there are financial, political or security issues abroad. However, these global flows will likely need to be channeled into mortgage assets through intermediaries, given the hesitance by foreign investors to directly invest.

The MBA paper outlines the following obstacles to foreign investors buying a larger share of MBS.

- Some foreign investors are banks and asset managers under similar constraints as U.S. banks and asset managers with respect to being measured relative to a benchmark index return.

- Official investors are even more likely to look for an explicit government guarantee before investing in dollar assets.

- MBS are complex securities to hold, hedge and finance. Many foreign investors are looking to intermediaries who can deliver more predictable cash flows from underlying mortgage assets.

- Foreign bank investors are constrained by Basel III and global systemically important financial institution (SIFI) rules as well.

Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) are, by virtue of the law that created them, subject to asset, income and distribution requirements that require 75 percent of their assets and income be connected to real estate and real estate finance. REITs can and some do have operating subsidiaries that originate or service mortgages.

Most mortgage REITs focus on holdings of agency and other MBS and use a combination of equity and debt to finance holdings of MBS. However there are more than 20 sizeable mortgage REITs with varying concentrations in agency and non-agency MBS, whole loans, MSRs and other mortgage assets.

Total mortgage REIT MBS holdings were roughly $300 billion in midyear 2014 and their leverage is typically 6:1 contrasted with 40:1 for the GSEs or more than 10:1 for banks. To grow their capital base, given the extreme limitations on retaining earnings, mortgage REITs need to return to the market through follow-on offerings.

Today, mortgage REITs debt funding is primarily from secured financing ("repo") of their mortgage assets from banks and other investors. Any larger role they might play in replacing the GSEs as owners of mortgage assets are restricted by a number of regulatory hurdles and concerns, primary among them the aforementioned regulatory concern about the stability of the repo market.

To increase the stability of their lending base some mortgage REITs have become members of the FHLBank system, usually through an insurance subsidiary. However FHFA has proposed eliminating this avenue of eligibility even though it is clear that mortgage REITs are financing home loans in a manner not dissimilar from other FHLB members.

Second, there are questions whether certain assets represent "interests in real estate." Failure to meet the required REIT asset and income tests can result in significant tax and other consequences.

Third, regulators have questioned whether the mortgage REIT model, utilizing limited leverage to realize an acceptable yield on a portfolio of mortgage assets, represents a new form of hidden leverage that could present a systemic risk. Fratantoni finds this judgment "odd". "A greater reliance on mortgage REITs would mean a larger share of the market for a set of institutions that have no government backing whatsoever, and hence represent truly private capital. While they are leveraged institutions, their leverage is less than that of other institutions investing in the mortgage market. And their positions are hardly in the "shadows" - by law, REITs must have a broad distribution of ownership interests, and many, if not most, are publicly traded."

That publicly-traded status means counterparties, regulators and the public has access to financial data on individual REITS and recent Commodity Futures Tracking Commission (CFTC) rules have also resulted in many mortgage REITs being required to clear their hedge positions, introducing yet another review mechanism. Moreover, mortgage REITs are overseen on a daily basis by their counterparties and post margin to support their positions.

As organizing and capitalizing a REIT is a well-understood process the sector could potentially be scaled up if some regulatory hurdles were removed the paper says. They are prime examples of private capital being deployed to hold and manage mortgage exposures and while some will fail during severe market disruptions, this is part and parcel of being fully private entities.

Fratantoni's conclusion is that there is no single player waiting in the wings to replace the Federal Reserve. The simple answer is that for sufficient yield, investors will come to the market. But perhaps we are headed for a new dynamic with higher and more volatile mortgage rates because there is no investor focused solely on MBS and other mortgage assets. Will this potential volatility "thin the herd even further?"

"Rebuilding the housing finance system to be both more stable and more competitive is a long-term endeavor," he says. "Identifying the barriers to private capital increasing its ownership of mortgage assets, and moving to reduce those barriers where feasible, should be part of the conversation and debate as we move forward."