A recent posting on the Urban Institute's (UI's) Urban Wire blog touched on six facts about the mortgage forbearance option mandated by the CARES Act for homeowners with federally backed mortgages. Some information came from weekly surveys by the Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA) and Black Knight and have been covered extensively here. These include the basis stats; 7.5 percent of all mortgages were in forbearance as of early August, a percentage that has dropped steadily from 8.9 percent in early June. The share of GSE loans in plans was 5.19 percent, Ginnie Mae (VA/FHA) loans 10.06 percent and the largest share at 10.12 percent was among loans serviced for portfolio lenders or private label securities (PLS). That last number is significant as PLS are not covered by the CARES Act, a situation that will be covered later in this summary.

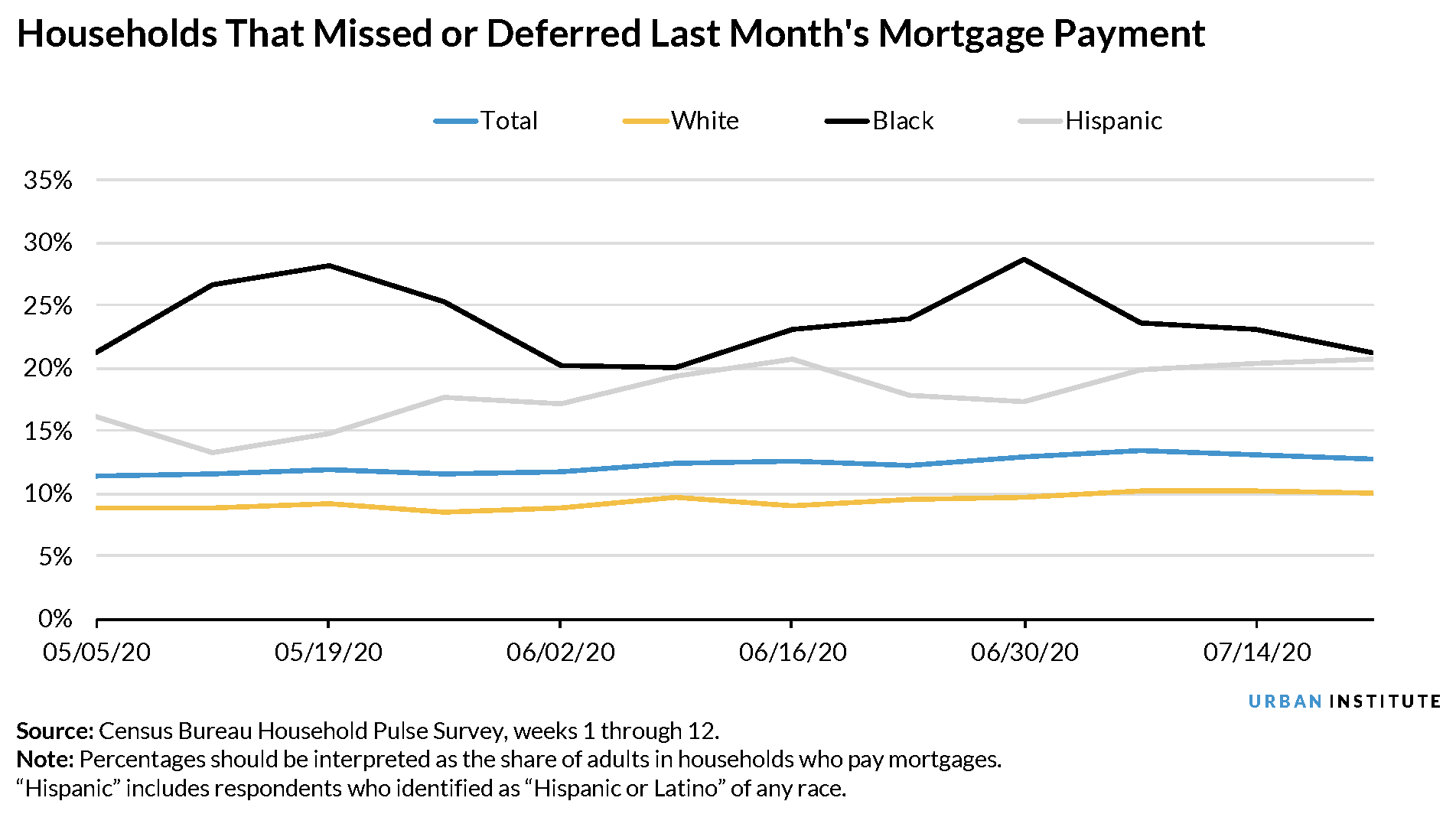

The article, written by UI analysts Jung Hyun Choi and Daniel Pang includes information from the U.S. Census Bureau's Household Pulse Survey which found racial disparities in the financial impact of the COVID-19 on the ability to manage mortgage payments. The most recent Census survey, conducted in mid-July, found nearly 21 percent of both Hispanic and Black households had missed or deferred the previous month's mortgage payment, compared with 10 percent of white homeowners and about 13 percent of all homeowners with payments due. This gap persisted over the duration of all survey weeks, as Black and Hispanic homeowners continue to be disproportionately burdened by the pandemic's impact on employment and financial stability.

The survey also found that fears about mortgage payments are growing. The federal unemployment insurance payments established by the CARES Act expired at the end of July and the survey found the share of households expressing "no confidence" in their ability to make their August mortgage payment reached almost 6 percent, its highest since the Household Pulse Survey began. That 6 percent includes 16 percent of Hispanic households and 8 percent of Black households but just 3 percent of white households.

Both the MBA and Black Knight surveys found about a quarter of those homeowners in forbearance continue to make their mortgage payments, a population about which none of the surveys provides much information. However, a survey by the National Housing Resource Center found that 530,000 homeowners have become delinquent since the pandemic began despite being eligible for forbearance. About 57 percent of these homeowners said they did not know about the forbearance option and 70 percent said they were afraid of making a lump-sum payment when the plan ends even though that is not a plan requirement.

There were an additional 205,000 borrowers in initial plans who did not extend them upon expiration, and subsequently fell into delinquency. There is little known about these homeowners or their decision-making process.

Choi and Pang say these facts point to the need to both provide more information to homeowners and to gather more information about them. There also must be preparation for what happens when forbearance ends. This includes tracking labor market conditions but also gathering more information on the financial and demographic characteristics by loan channel of those in forbearance to help them choose their best option to pay back their deferred mortgage payments.

This will be challenging but not impossible. Servicers could provide some of this information, and the Census Bureau could add a question regarding the household's forbearance plan status when the Household Pulse Survey restarts later this year. Together with the variables about households' housing payments and demographic and financial characteristics, the additional question could lead to understanding households who are not taking advantage of forbearance and give decisionmakers a better sense of what supports could best meet their needs.

In a separate UI blog piece, Karan Kaul looked at some of the unique problems involved in forbearance for households with PLS/portfolio loans, which are not covered by the CARES Act. While better than 10 percent of the 14.6 million borrowers with those loans have been granted forbearance, Kaul says providing the same kind of assistance as has been offered to GSE/FHA/VA financed homeowners is challenging.

Federally financed homeowners can obtain forbearance under standard terms dictated by the guarantor. However, PLS/portfolio borrowers receive it with varying durations, qualification requirements and repayment options. This means that two borrowers with similar circumstances may get different treatment because different entities own their loans.

Kaul says a recent UI event focused on PLS loans and the economic and legal hurdles to equal treatment for servicing them. The event found a lack of standardization in the Pooling and servicing agreements (PSAs) that spell out servicing, rules, particularly as to which entity holds the legal authority to decide the terms of loss mitigation. It can be a particular investor or the servicer, trustee, or bond administrator. This is problematic because each of these entities may have different contractual constraints or discretion regarding loss mitigation decisions. Even where contracts provide direction concerning loss mitigation, there can be different interpretations of similar language.

Even where PSAs dictate what the servicer can do, there is often a lack of specificity that addresses every possible circumstance. This may apply to the current pandemic which is not covered in most PSAs because no one expected it to happen. A PSA that may allow forbearance might not specify the duration, eligibility, repayment, or other terms. It may be difficult to decide how to divide the reduced cash flows to the multiple PLS tranche holders, how to handle the repayment of the forborne amount or the value of interest lost until the arrearage is repaid.

Servicers have a contractual obligation to the investor that can conflict with doing right by the borrower and providing CARES Act-type forbearance. Should investors receive diminished cash flows, the servicer could be held liable for damages if it constitutes a contractual breach.

Kaul says they issues don't affect agency mortgages because the GSEs, FHA, and the VA are the decisionmakers and the government bears the cost of their decisions. In the PLS world, one entity could be the decisionmaker, but the decision's costs could be spread among many others. While agency servicing guides are updated frequently to address new circumstances as has happened during the pandemic, PSAs are locked once they are written at the time of origination.

The most effective policy solution would be to align borrower treatment across non-agency and agency channels, but the structure of PLS servicing is fragmented fundamentally and different from the agency space.

If this sounds familiar, Kaul points out these PLS loan servicing challenges were at the forefront of the Great Recession and caused significant consumer harm. While one UI event participant told Kaul that the PSAs for newer PLS deals "are much better than they were in the last crisis," about 1.6 million loans, or 61 percent of the 2.6 million PLS loans outstanding today, were originated before 2009. Before the Great Recession, PLS borrowers had weaker credit characteristics and higher default rates. Since 2009, more stringent underwriting standards have markedly improved the credit characteristics of PLS loans.

Participants at the UI event offered several suggestions to break down the structural and systemic barriers that are causing disparities in borrower treatment.

- Grant forbearance rights to PLS borrowers. The Health and Emergency Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions (HEROES) Act, which has passed the US House of Representatives guarantees 12 months' forbearance for 100 percent of the market, including PLS loans. This would give PLS borrowers the same relief as those with federally backed loans. The Act also includes a liquidity provision to help servicers address cash flow issues while providing forbearance. The Senate has not taken up the HEROES Act.

- Reestablish loss mitigation infrastructure. Better communication and coordination could provide borrowers and housing counselors with better access to PSAs so they can thoroughly understand their options. This could be done by reestablishing Great Recession infrastructure such as the HOPE Loan Port and HOPE NOW Alliance.

- Increase PSA standardization. Participants supported facilitating standard, transparent interpretation of PSAs across servicers to reduce variability in borrower treatment. A bondholder communication platform could facilitate the efficient flow of information to and from investors and speed up decision making. But it is also clear that these changes will not happen automatically.