One of the trends in attempts to provide more affordable housing is the growth of accessory dwelling units (ADUs) such as granny flats, garage apartments, or in-law suites. These aren't a new thing, Freddie Mac points out, in a research paper on the subject, that Fonzie occupied an above-garage apartment at the Cunningham home, but they have been somewhat invisible, and often illegal.

The invisibility was often linked to their illegality. Zoning laws passed during the postwar rise of suburbs often limited construction of high-density housing and because so many ADUs were built against city ordinances, without required permits, little research literature was published. Freddie Mac could account for only three or four papers in the 1980s and 1990s and they were mostly small in scale and based on limited data.

The data for the new paper was gathered from property descriptions on Multiple Listing Service (MLS) boards. It looks at the growth of these units, the various structural types of ADUs in use (both permitted and illegal) and discusses the measurable benefits of having ADUs in our communities.

ADUs are broadly defined as secondary, self-contained housing units located on the same lots as the primary single-family home. Size and structural form vary, but in most cases, ADUs include the following amenities: a bathroom, kitchenette, living area, and separate entrance

Freddie Mac's Economic and Housing Research Group, which authored the paper, said the biggest challenge of collecting ADU data from MLS unstructured text was understanding the multitude of terminology and physical forms applicable to ADUs in different locales. In addition to the three mentioned above, these included guest cottage, guest quarters, carriage house, separate entrances, and a number of variations using either in-law or garage.

The authors mined a national database of 600 million MLS transactions dating back to the late 1990s, Once the terms were identified, parsed into different parts of speech and frequency distributions determined, they were left with a total of 1.4 million distinct single-family properties with accessory dwellings.

Prior studies on numbers of newly built ADUs have typically used building permits, but that data is for permits issued, not units completed. Also, illegal or shadow housing is not represented in the data and most studies agree those are prevalent in neighborhoods that lack affordable housing. A 2009 field survey of three foreclosure plagued neighborhoods in Los Angeles found that 34 to 80 percent of the single-family houses were likely to have illegal ADUs. A survey in San Francisco in 2011 found that more than 90 percent of secondary units lacked building permits.

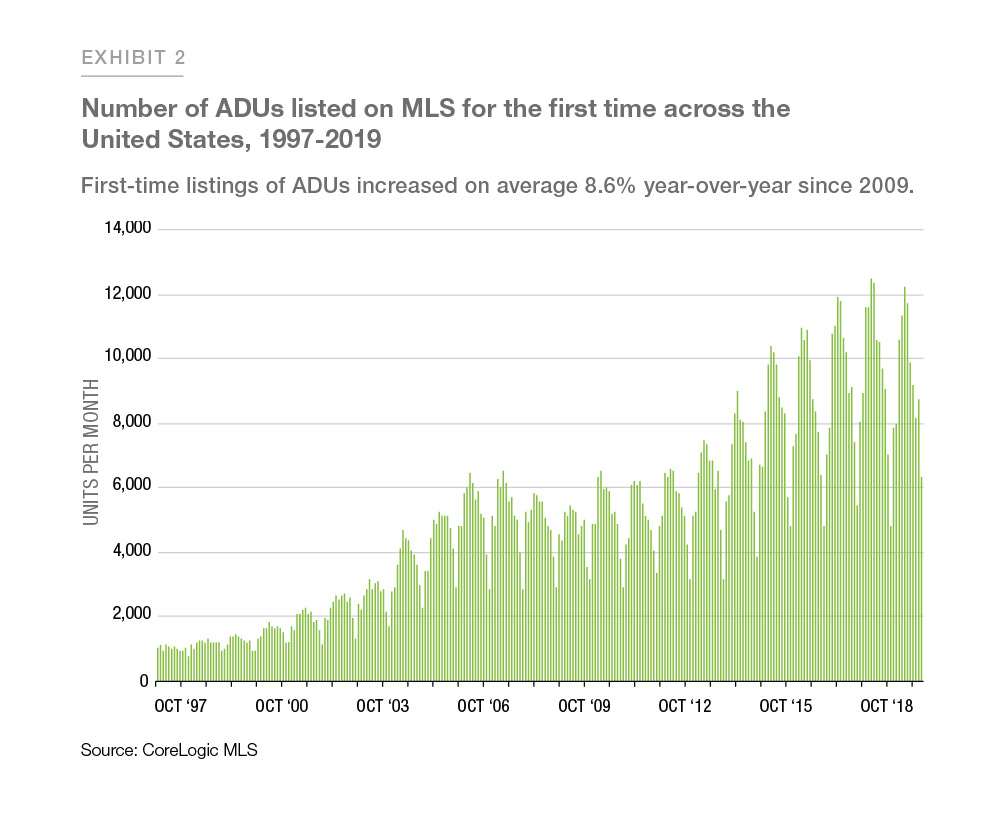

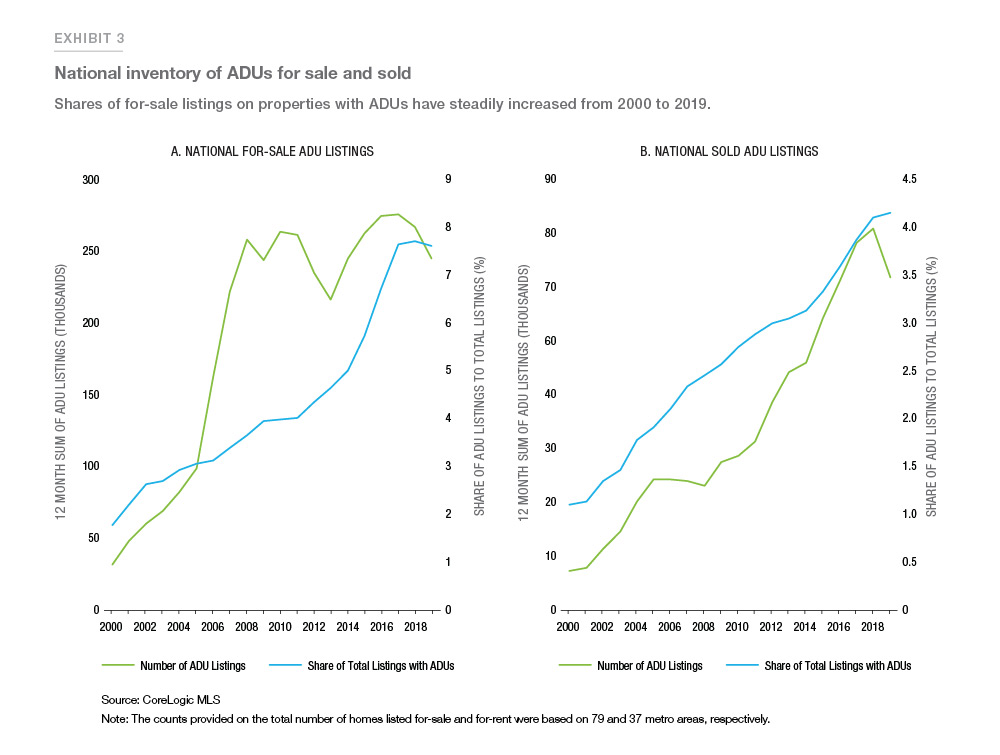

Using first-time listings on MLS, Freddie Mac estimated that there was a national growth rate of ADUs averaging 8.6 percent annually between 2009 and 2019. They found additional evidence of a rise in supply and demand by looking at the percentages of total homes listed and closed. In 2000, 1.6 percent of active MLS listings had ADUs. That grew to 6.8 percent in 2019.

In terms of numbers sold, less than 9 thousand or 1.1 percent of homes sold on MLS in 2000 had ADUs. By 2019, sales of homes with ADUs grew to nearly 70 thousand or 4.2 percent.

From 2003 to 2019, the percentage of active rental listings increased from 1.8 percent 4.1 percent and the number of leased rental listings increased from 1.2 percent to 2.9 percent.

Freddie Mac admits that their research methods has several sources of error. If, after construction is completed, owners hold on to their units, rent or sell them outside of MLS, or the listing descriptions do not match search phrases, then activity will be understated. Overstatement bias will occur when existing, older units are listed for the first time on MLS. However, these figures are backed by permit data from numerous "ADU-reformed" cities. By "ADU-reformed," Freddie Mac means cities where ordinanes have been pased to reduce restrictive zoning.

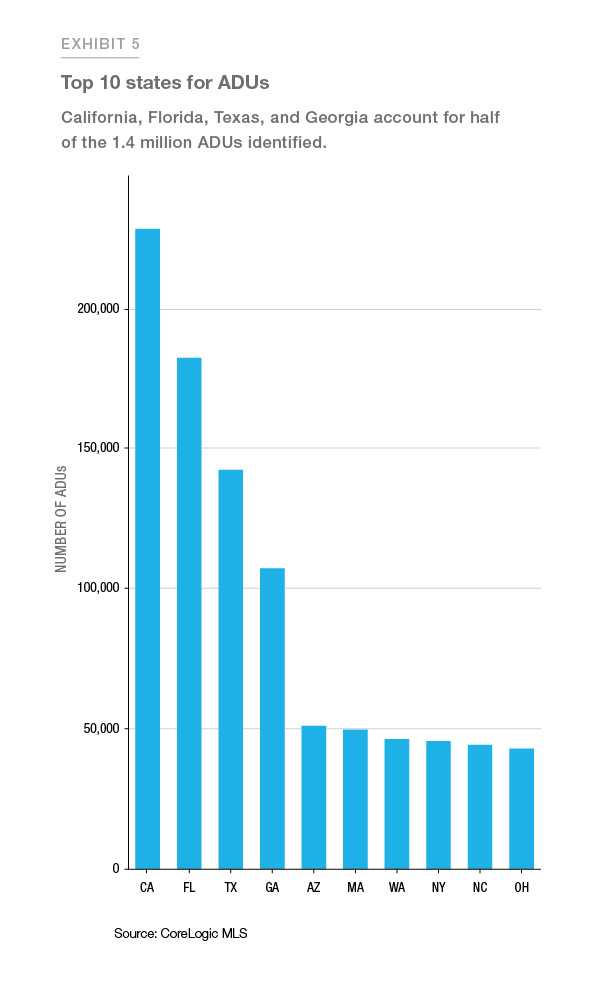

The demand for accessory dwellings is highest in the fastest growing regions of the country and population growth, in both absolute numbers and percentages has been overwhelmingly higher in the South (11 million net increase; 9.6 percent growth) and the West (6.4 million and 8.9 percent) according to Census Bureau estimates for 2010 through 2019. The number of for-sale listings that mention ADUs has risen correspondingly, increasing in the Sun Belt (from 4.3 percent in 2010 to 9.2 percent in 2019) faster than in the North (2.7 percent to 4.1 percent). Similarly, shares of sold listings for those homes rose in the Sun Belt from 3.2 percent to 5.6 percent while in the Northern they increased from 2.2 percent to 2.6 percent. Half of the 1.4 million ADUs Freddie Mac identified are in the Sun Belt states of California, Florida, Texas, and Georgia.

The same trend was observed in rental listings and for leases. The share of the latter declined slightly in the North.

Drilling down to metropolitan-level detail, 23 of the top 25 metro areas with the highest number of first-time ADU listings occurring between 2015 and 2018, are in the South and West regions. Portland, Dallas, and Seattle metro areas rank highest in terms of year-over-year growth, at 22.3 percent, 18.8 percent, and 17.5 percent, respectively.

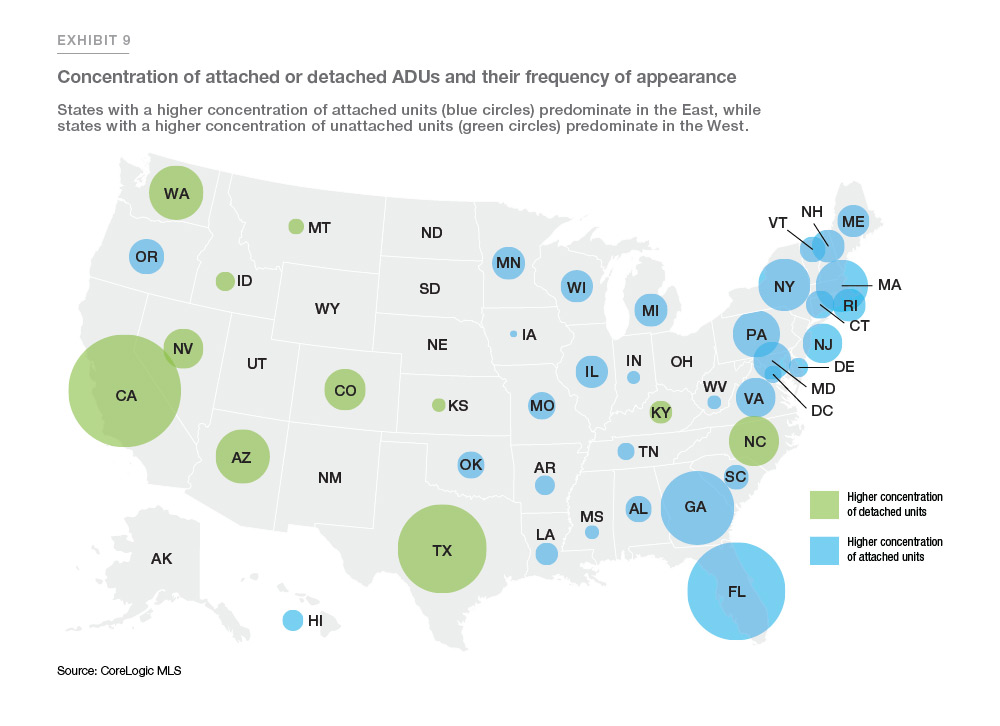

The authors also looked at the ways in which ADUs are produced in different parts of the country. They can be attached or detached, carved out of interior space, or connected to the main structure such as basement apartments or above garage units. Others are free-standing, such as guest cottages and carriage houses, typically located in a backyard or over a detached garage.

In Exhibit 9, states with green-shaded circles have higher shares of detached ADUs, while states with blue-shaded circles have higher shares of attached ADUs. The highest concentrations of accessory dwellings, as noted by the size of the circles on the map, are located mainly in coastal regions, where most of U.S. households reside. As expected, detached ADU housing stock occurs more prevalently in sprawling western cities, characterized by large, low-density lots and plenty of open space. Homeowners living in older, denser industrial cities along the East Coast, by contrast, are more land-constrained and more commonly create units through conversion of existing space in basements or attics.

Opponents of ADU development argue that they mainly serve as extra living spaces, offices, or sources of short-term rental income for the owners, not long-term housing for additional families, however, a survey of ADU owners in Portland, Oregon in 2013 found nearly 80 percent of units were used as long-term residences. Costs to build an ADU were also significantly cheaper in Portland than traditional single-family housing because no extra land needed to be purchased. The median cost of attached units was $45,500 and the median cost of detached units was $90,000. Portland's median home price at the time was $290,000. At less than one-third of the price of traditional primary residences, ADUs are an affordable alternative for families wishing to provide living spaces for family members who are elderly, young adults, or single.

Freddie Mac tested whether the same long-term use applied to other locales and found about 40 thousand repeat or paired rental listings between 2015 and 2018. About three quarters were in Texas, California, Florida, Georgia, and Arizona. The median number of days between paired listings in these 5 states ranged from 262 days to 371 days, and shares of short-term rentals-defined as properties reposted in less than 30 days-ranged from 7 percent to 15 percent. These estimates do not account for properties that are solely posted on short-term rental sites. Nonetheless, the results support the view that ADUs are helping to fill the gaps in long-term affordable rentals.