The Government National Mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae) is the agency, housed under the Department of Housing and Urban Development, that converts government guaranteed mortgages into mortgage-backed securities for investors to purchase. Their originations are 57 percent FHA loans, 40 percent VA loans, and 3 percent loans from other government programs, primarily the Department of Agriculture.

For several years, as we have written about here, Ginnie Mae has been concerned about the significantly higher rate of repayments of the VA loans in its portfolio when compared to those originated by its other guarantors and to the government sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae.

Some of the increased speeds result from the lower costs of refinancing a VA mortgage compared to other types and VA borrowers tend to have better credit score than those with FHA, making refinancing easier. But some of the faster prepayments are due to "churning," that is, a lender makes the original mortgage with the expectation that the loan will quickly refinance. Such rapid refinancing is often detrimental to the borrower who may pay an above market rate for a period of time and additional origination fees on the new mortgage.

Where the refinancing includes cash-out, the increased balance includes both the fees and some equity taken out for the borrower. New cash-out refinance mortgages were 24 percent of VA originations in March 2019 but just 20 percent of Freddie Mac and 17 percent of FHA originations (Fannie Mae data are unavailable).

Prepayment speeds are difficult to quantify as there are variations based on the servicer, borrower characteristics, and whether the loan was for purchase, rate and term or cash-out refinancing.

Ginnie Mae has stated that the higher repayment speeds of VA mortgages are raising the cost of all government mortgages and may be damaging investor confidence in Ginnie Mae's product. Three Urban Institute researchers, Laurie Goodman, Ed Golding, and Michael Neal have published a paper attempting to quantify those costs.

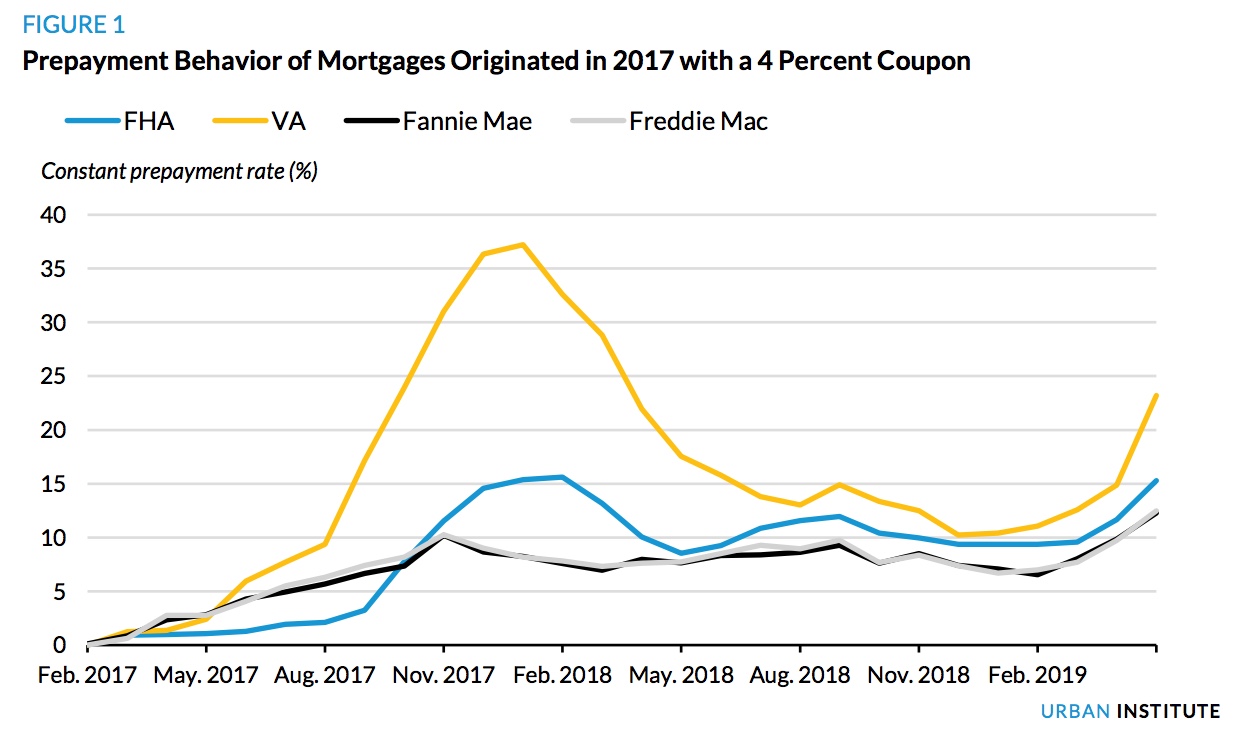

They confirm that VA borrowers prepay their mortgages faster and are more responsive to interest rate declines than those with mortgages either FHA or the GSEs. The figure below illustrates the prepayment behavior of VA mortgages versus FHA and conventional mortgages pooled in 2017 with a 4 percent coupon.

VA lenders that churn loans do so because they can make a profit with two closings but refinancing a loan that has already been securitized is costly for investors in mortgage-backed securities. For example, Goodman et. al found that, if a borrower takes out an FHA mortgage with a 4.25 percent interest rate, that mortgage will be packaged in a securitization with a 4 percent coupon. The servicer will keep 19 basis points for servicing, and Ginnie Mae will receive 6 basis points. If all Ginnie Mae 4 percent $100 par mortgages are priced at $103.50, each one that is refinanced into an identical mortgage right after purchase will cost the investor $3.50 per $100 invested. The investor is compensated for this risk by receiving a rate higher than the Treasury interest rate on a guaranteed security, but the more loans that are removed and refinanced, the more investor confidence in this security is undermined.

The authors say that borrowers prepay at different rates and have difference incentives for refinancing, but lower rates generate more activity. They made several assumptions for their calculations.

- The Ginnie Mae pool composition is 40 percent VA loans.

- The VA has a 15 percent faster conditional prepayment rate in the first year, a 10 percent in the second year, and 5 percent in the third year. These numbers are larger than the averages in Figure 1. For purposes of the study they assume FHA speeds are zero, and the results are not discounted.

- The current price of a Ginnie Mae 4 percent mortgage pool is $103.50.

If all mortgages prepaid at the same speed as those backed by the VA the cost to a Ginnie Mae investor would be 15 percent in year one and 10, and 5 percent of the declining balances in each of the next two years. This would be multiplied by 3.5 percent representing the $3.50 cost of a $100 security. The result is $0.95 of each $100 of mortgage balance. However, since VA mortgages make up only 40 percent of the pool, the cost to investors would be $0.38 per $100 par value.

If this were passed through to borrowers, they would have to pay an additional 7 basis points per year in interest rates to cover this risk. This would increase the monthly payment on a $250,000, 30-year mortgage by $175 a year. Because many of these prepayments do not benefit borrowers and represent an abuse of the program by lenders, this extra cost is more concerning than the numbers might indicate.

All Ginnie Mae borrowers pay higher interest rates because of high VA prepayment speeds. The impact is greater for borrowers who are less apt to refinance, typically borrowers with low credit scores and those who live in areas with low home price appreciation. Critically, the cost to all borrowers could be larger if investors lose confidence in Ginnie Mae securities because of churning.

Ginnie Mae has taken several actions to curb abuses since 2016. It implemented a six-month seasoning period for refinance loans and later extended this to cash-out refinance loans. In 2018 it put lenders with fast VA speeds in a "penalty box" for various periods by prohibiting those lenders from delivering VA loans into large multi-issuer Ginnie Mae II securities. That year the VA implemented a net benefit test to ensure veterans receive some benefit from refinancing. Even so, VA speeds are still faster than FHA or conventional speeds.

In May Ginnie Mae issued a request seeking advice on further action and, although the deadline has expired, comments are still welcome. Ginnie Mae specifically asked for comments on prohibiting or restricting the amount of VA cash-out refinances with a loan-to-value ratio over 90 percent that can be pooled with other types of loans. The authors say however that such a restriction would have a marginal effect on speeds and not close the gap relative to FHA or government-sponsored enterprise mortgages. The bigger question is how much variation in prepayment speeds can be allowed in the Ginnie Mae program and how much of the variation is attributable to inappropriate practices.

The next step is less clear. The request for information has probably generated suggestions to exclude certain loans and this will have implications for borrowers and prepayments. The authors say Ginnie Mae should first understand who is using any products that might be excluded or restricted and test what the effect might be on outstanding pools. Other options might include the VA strengthening the net benefit test on refinancing; an explicit calculation revealing borrower gain. Ginnie Mae might resort to further restricting the ability of refinancings on recent originations to be placed into Ginnie Mae securities. A more extreme action would be issuing separate securities for VA loans. The paper concludes that any of these options could impose significant costs on the mortgage system and create winners and losers. "Nonetheless, doing nothing is not a good option."