Happy Anniversary - or something...

It is a decade since the financial crisis and ultimately the Great Recession began. Bear Stearns collapsed in March of 2008, the government sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, were placed in conservatorship in August, and AIG, Goldman Sacks and many other banks were "rescued" by the U.S. Treasury in September.

Much of the blame for triggering the events was laid at the feet of the housing industry. Now, ten years later, the economy is booming but housing is a bit of a mixed bag. Robert Abare, editor of the Urban Institute's (UI's) Urban Wire recently interviewed UI research associate Karan Kaul, getting his assessment of the housing market's status ten years later.

Kaul says the flawed regulations and lending practices that the market crash revealed have mostly been addressed, but some, like GSE reform, remain and other responses have been too severe, contributing to new problems.

He said that GSE reform, or the lack of same, gets a lot of attention, but the most pressing issue is the lack of new home construction. The improving economy means more and more young people are creating more than one million new households every year, but the nation is adding only a net of about 800,000 housing units. "This gap pushes house prices up, leading to many potential homebuyers being priced out of the market," he said. "This means more families remain as renters, driving rents up significantly. This makes it more difficult for renters to save for a down payment."

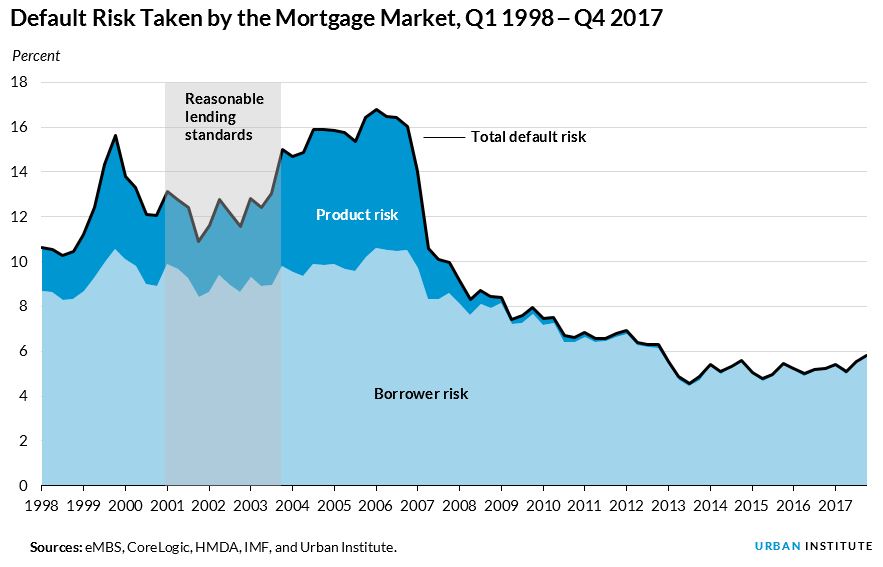

So how can these potential homeowners be helped? Kaul says access to mortgage credit remains too tight. While pre-crisis lenders were making loans to people who couldn't really afford them, now the pendulum has swung too far the other way. The default rate on loans originated today are as low as they can possibly get.

Lenders are wary about lending to riskier borrowers, in part because the higher costs of origination and servicing has shifted the profitability equation for lenders, making lending to less than pristine borrowers much more expensive. Kaul's assessment was born out by the Mortgage Banker's Association report on Wednesday that the average independent mortgage banker lost money in the first quarter for only the second time since 2008.

The origination process has become more time consuming and thus expensive because of the process involved in collecting volumes of information and documentation from borrowers, then verifying everything. Lenders paid big fines for originating faulty loans during the bubble era so now they double- and triple-check everything to make sure the loan file is accurate. This costs money.

Mortgage servicing costs have changed drastically as well, partly due to enhanced regulation, but also to changes within the industry itself. Servicing was once a back-office operation; processing payments, keeping track of late fees, paying insurance and taxes from escrowed funds. But, as the housing crisis unfolded, Kaul said, servicers learned they needed to reach out to struggling borrowers and understand their circumstances and why they may have fallen behind on payments and then offer options to help them deal with these different situations. What is referred to as "high touch" servicing is very expensive and became much more common during and since the crisis.

To mitigate the high costs of origination and servicing, lenders try to avoid making loans with a higher likelihood of defaulting. If the loan defaults, the amount of money a lender must spend on that loan is exorbitantly high. At the same time, many otherwise creditworthy borrowers are barred from homeownership because of uneven income streams resulting from self-employment or working in the gig economy, a problem that is not being addressed.

Kaul offers some solutions. First, to boost the supply of housing there should be a closer look at how land development and zoning regulations are disincentivizing new home construction. "It can take years for builders to get permits, and the longer it takes to get a permit, the more expensive it becomes to build. Manufactured homes, for which production is expected to gradually increase, can also be a part of the solution."

He also suggests addressing the rising cost of originating and servicing loans through technological advancement. He has written elsewhere about so-called fintech non-banks which lend using technology platforms . A study from researchers at the Federal Reserve found that they reduce loan processing time by an average of 10 days, a 20 percent reduction. Creating more certainty for lenders would also allow them to save on quality control costs. Other strategies like encouraging small-dollar mortgages can help expand homeownership to those with less than perfect credit.