CoreLogic's analysts continue to report on the validity of appraisals. A blog entry from last December found that thirty percent of appraisals the company reviewed were at the contract price while 60 percent were above it. A new article, written by Yanling Mayer, looks at the use of comps, especially how they are adjusted, as a factor in this valuation pattern.

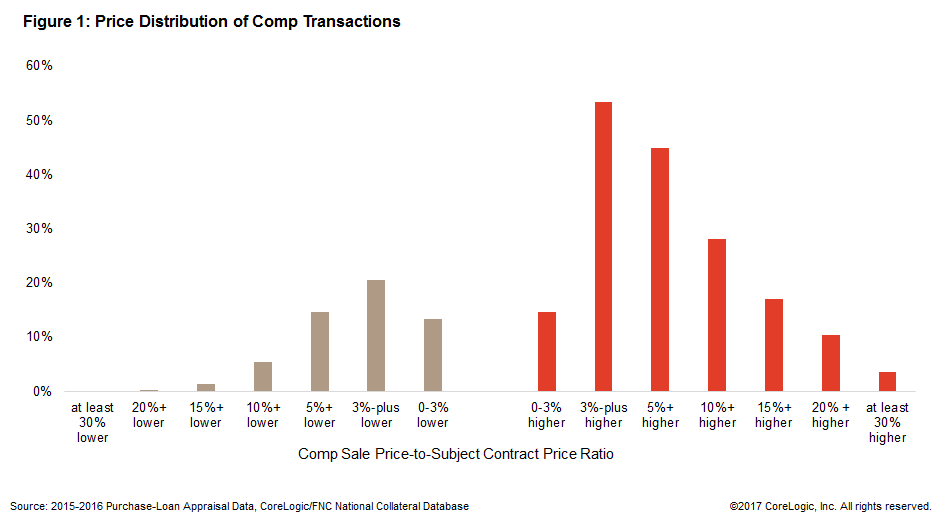

A recent review of three-quarter million purchase-loan appraisals completed in 2015 and 2016 showed 69.1 percent of the comps used in those appraisals were priced higher than the subject property and 30.9 percent were priced below it. The average difference between the subject and the more expensive comps was 12 percent while the less expensive ones were 6.4 percent below.

A prevalence of higher-priced comps could lead to higher-than-purchase-price appraisal conclusions, but value adjustments to make the comp similar to the subject could, and in fact is supposed to, negate this effect. Adjustments that are inadequate to inconsistent, Mayer says, could partly explain why appraisal valuations tend to come in higher than the subject's contract price.

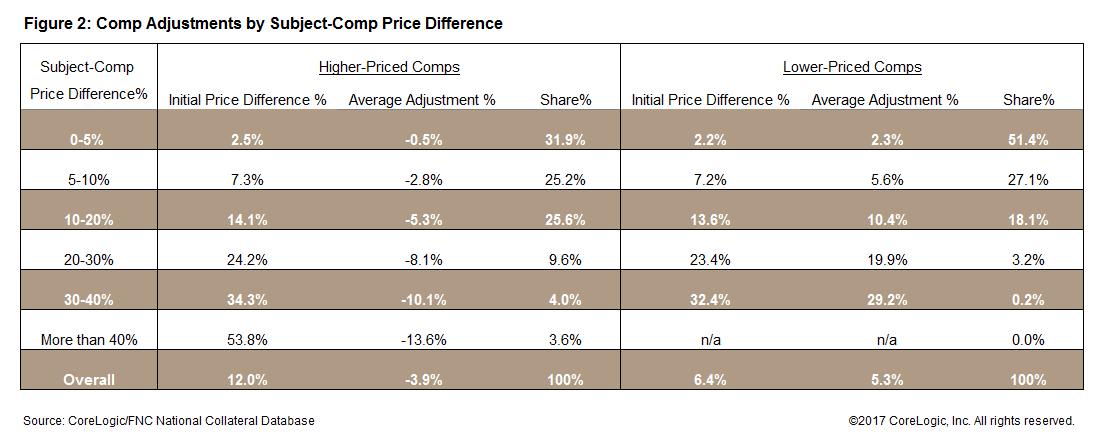

The CoreLogic analysis divided comps into two groups to reflect their final value was higher or lower, than the sales price. Then, within each of the two divisions, the comps were groups by the price difference, whether higher or lower, between it and the subject, by 0-5 percent, 5-10 percent, 10-20 percent, 30-40 percent, and more than 40 percent. The larger the price gap, Mayer says, the more likely there are greater physical and economic dis-similarities between the two, thus requiring a larger price adjustment.

Figure 2 shows the Initial Price Difference (i.e. the variance between the comp and the subject property before any adjustment) and the Average Adjustment received by each price grouping. The analysis found two distinct patterns. The percentage of the Average Adjustment to lower comps tends to be much larger than those given to the higher comps. For instance, in the 20-30 percent deferential groupings the higher comps were adjusted down by an average of 8.1 percent while the lower-price comps were adjusted upward by 19.9 percent. Mayer says the 19.1 percent upward adjustment appears in-line with the 23.4 percent pre-adjustment difference while the 8.1 percent downward adjustment is only a third of the original price differential. This pattern holds for the other groupings as well.

Second, as the subject-comp differential widens, the adjustment in the higher price groupings does not keep pace. For example, the initial price in the 20-30 percent higher group averages 24.2 percent and rises by 10.1 percentage points moving into the 30-40 percent group. However, the downward adjustment increases by only 2 points. In contrast, adjustment in the corresponding groups of lower comps rises, from 19.9 percent to 29.2 percent, close to matching the 9+ point rise in initial prices.

Mayer concludes that, by themselves, these patterns aren't sufficient to make conclusions at the loan level; more research is needed. However, he says, "They do reveal aspects of underlying inconsistency in the appraisal development, for which more sophisticated data analytics techniques are likely better suited. Undoubtedly, as the industry continues to embrace the opportunities that new data and technology have presented, traditional appraisal will likely incorporate big data techniques to position itself as a superior, unique alternative to automated valuation models."