Two noted economists seem to be holding little hope that Congress will take up in any way changing the status quo of the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) before adjourning next January. However, they say it is an issue on the Trump Administration agenda and they expect the Executive Branch will step into the fray. In a paper published by the Urban Institute titled GSE Reform is Dead - Long Live GSE Reform, Jim Parrott and Mark Zandi ask, if Congress does fail to address GSE reform, what will the executive branch do with the opportunity?

Parrot is a nonresident fellow at the Urban Institute. He owns Falling Creek Advisors, a financial institution consulting firm and previously served as White House senior advisor on the National Economic Council.

Zandi is chief economist of Moody's Analytics, where he directs economic research and frequently comments on monetary and fiscal matters to major news media outlets. Among his published books is Financial Shock: A 360º Look at the Subprime Mortgage Implosion, and How to Avoid the Next Financial Crisis.

The most important player in any reform of the GSEs will be the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), the regulator and conservator of the GSEs Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The two privately held corporations were placed under federal conservatorship in August 2008 and remain there despite both returning to profitability in 2008.

The term of the current director, Mel Watt, will expire in January so the administration will have the opportunity to appoint a new one, undoubtedly an individual who will share their vision for GSE reform. The authors say, given the current ideology, that individual will probably take steps to reduce the GSEs footprint in the housing finance system. Also, given the administration's public commitment to ending the conservatorship, the Treasury Department could work with FHFA to release the GSEs.

The authors look at both issues and we will summarize their analysis in two separate articles. This one will look at the options for shrinking the current GSE footprint in the market. A second will explore some of the ways in which the current GSE/government relationship might be altered or eliminated.

Conservatives have long been critical of the role the GSEs play in the housing finance system, placing significant blame on them for the housing crisis and bemoaning their outsized influence since then. They make the argument that they distort the market and create excessive taxpayer risk. Thus, it should be expected that a new director will take steps to reduce this market role.

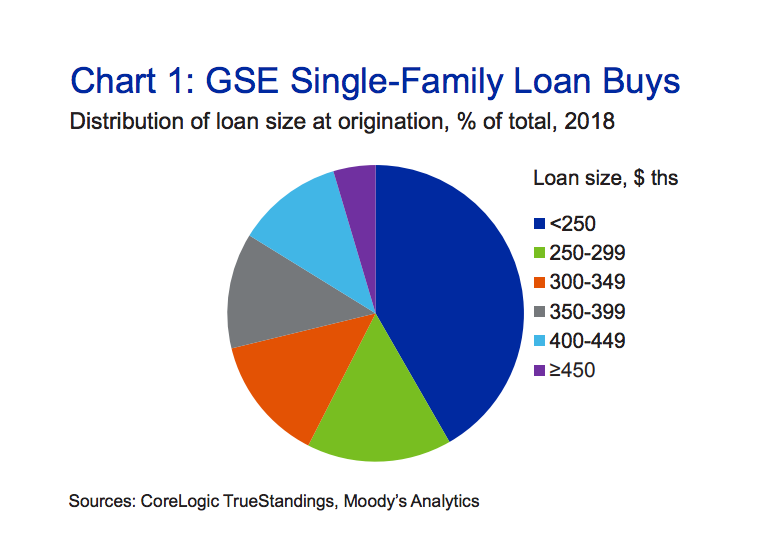

The most direct way to accomplish this would be to gradually reduce the conforming loan limits. The current ceiling is $453,100 in most U.S. counties but can reach as $679,650 in high cost areas. Reducing the limit would shrink the GSE footprint in high income areas, using the rationale that they are the least in need of government support. Eliminating the outlying higher limits could cut GSE loan volume as much as 5 percent; reducing the standard limit to $350,000 could cut it by one quarter. While this would violate many legislative rules regarding the limits, Parrot and Zandi go into detail as how this could be done.

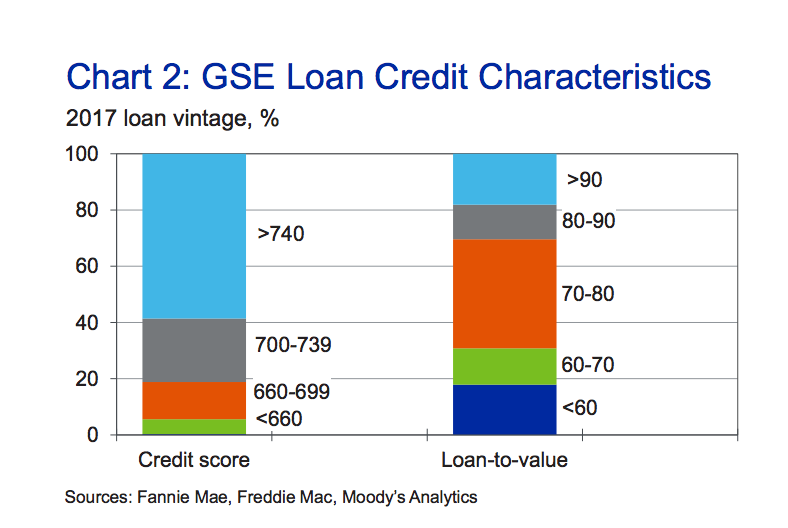

A second path would be to tighten minimum credit requirements, for example reducing the loan-to-value ratio, debt-to-income levels and raising the credit scores for loans eligible for GSE purchase or guarantee.

Either aggressively reducing loan limits or tightening underwriting standards would be disruptive, but in different ways. A loan limit change could leave entire neighborhoods with less access to credit, possibly all at once. While portfolio lenders might pick up some of the slack, borrowers who don't fit into their boxes would face higher mortgage rates. Tightening credit would push a large number of borrowers into subsidized government lending channels like FHA which might, in turn, increase taxpayer risk.

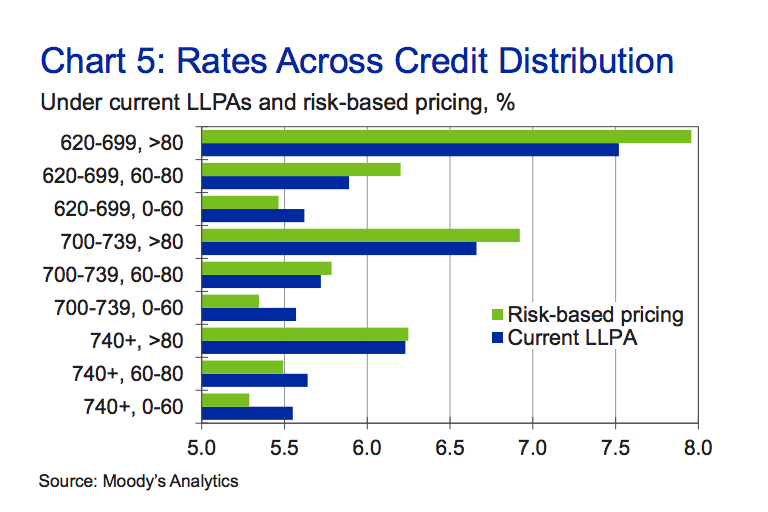

Yet a third way to reduce the GSE footprint would be to gradually raise the fee charged for their guarantee. This is currently at about 60 basis points for all 30-year fixed-rate mortgages (FRMs) The GSEs also charge a loan level price adjustment, of anywhere from 25 to 375 basis points on higher-risk loans. FHFA could require the GSEs' to raise either or both of these fees and the impacts would differ with their choice. Boosting the overall guarantee fee would entice many lower risk borrowers to move to a portfolio lender or FHA. Increasing the LLPAs would cause the GSE footprint to shrink at the bottom end of the credit spectrum, pushing higher-risk borrowers toward FHA as well.

Finally, the GSEs could be required to pull back on the types of loans they purchase. Conservatives argue there is no public policy reason for the GSEs to do cash-out refinancing, which accounted for 20 percent of their loan volume last year, or to make investor or second home loans. Those constituted another 10 percent.

The choices of how to reduce the GSE footprint will depend on which part a conservative FHFA wants to shrink and the type of market disruptions it is willing to endure. The authors say it is relatively certain it will use a mix of each to shrink the GSE role in single-family housing and probably will consider ways to reduce their role in the multi-family sector as well.

Multifamily lending has increased over the decades and the GSEs now account for almost half of all outstanding loans of that type. The GSEs have seemingly avoided some of their single-family lending mistakes in this sphere so there appears to be less pressure to shrink or eliminate that portion of their businesses. However, the authors expect at least some consideration to be given to reducing origination volume caps to more narrowly target such lending or even to spin the multifamily businesses out of government control altogether.

Some conservatives have also criticized the cross-subsidy the GSEs provide. Freddie and Fannie charge lower risk borrowers more than their risk levels would dictate so higher risk borrowers could pay less than theirs would imply. This policy is intended to put more loans in reach of more borrowers, meet the GSEs' housing affordability goals, and allow them to fulfill their mandate to serve rural and manufactured housing markets. The cross subsidy is estimated at $3.8 billion per year.

Critics argue the cross subsidy is unfair to lower-risk borrowers and that it places excessive risk into the system. They even have even blamed the GSEs affordability goals in part for the financial crisis. They also argue that those goals increase demand and push home prices higher, making them unaffordable to those the system is designed to serve. The authors say these claims have been consistently proven incorrect, but they remain central to conservative narratives.

A new director is likely to change this as well. At the extreme, FHFA could push the GSEs into full risk-based lending, significantly increasing LLPAs while lowering guarantee fees for low risk borrowers.

If the GSEs were required to remove the cross-subsidy and fully enact risk-based pricing they would siphon off some lower-risk borrowers from portfolio lenders and lose some higher risk borrowers to the FHA or other more heavily subsidized channels of government support.

In taking this step, the next FHFA director would also likely roll back the affordability goals and duty to serve requirements to an extent that the GSEs could easily meet them without needing a cross-subsidy. While the FHFA is mandated by HERA to set these requirements, the director has enough discretion to set them in a way that has little effect.