A paper just published by The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston is bound to generate a lot of comment both inside and outside of the mortgage industry. Titled Why Did so Many People Make so Many Ex Post Bad Decisions? The Causes of the Foreclosure Crisis, the paper presents 12 facts about the mortgage market which the authors say refute the conventional wisdom that the housing crisis resulted from financial industry insiders deceiving uninformed borrowers and investors.

The authors, Christopher L. Foote and Paul S. Willen, senior economists at the Boston Fed and Kristopher S. Gerardi , a research economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, argue that borrowers and investors made decisions leading up to the crash that were rational and logical given their ex post overly optimistic beliefs about house prices and that neither institutional features of the mortgage market nor financial innovations are likely to explain those distorted beliefs. "Economists should acknowledge the limits of our understanding of asset price bubbles and design policies accordingly."

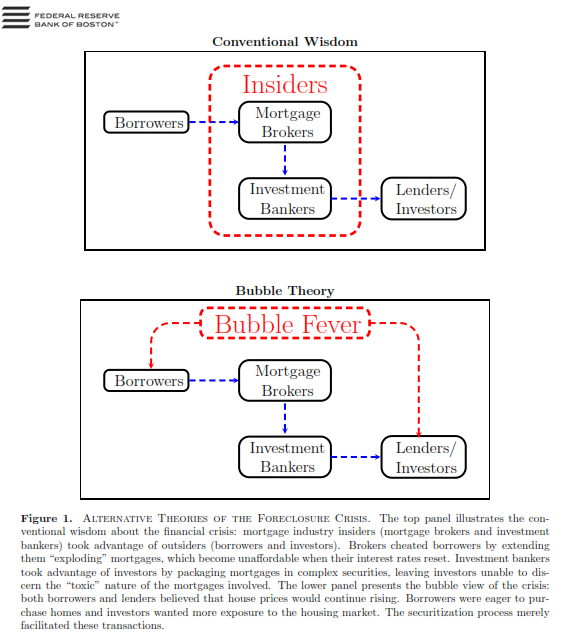

There are two general explanations for the mortgage crisis. The insider/outsider explanation, the most dominant one, is that well-informed mortgage insiders used the securitization process to take advantage of uninformed outsiders. This story paints a mortgage broker convincing a borrower to take out a mortgage that initially appears affordable but with an interest rate wired to explode a few years later, throwing the clueless borrower into default. The mortgage broker does not care about the risks because he is passing the mortgage on to an investment banker who then includes it in a mortgage-backed security. The banker intentionally uses excessively complex financial engineering to dupe the investor about his investment. When the loan explodes the borrower loses his home and the investor loses his money but the broker and the banker have no skin in the game and thus suffer no losses.

The second theory does not draw a line between insiders and outsiders but depicts a "bubble fever" infecting both. If each believes that house prices will continue to rise rapidly then it is not surprising to find borrowers stretching to buy the biggest house they can and investors lining up to give them money. Rising house prices generate capital gains and insulate investors against losses. If this alternative theory is true then securitization was not the cause of the problem it merely facilitated transactions that borrowers and investors wanted to undertake anyway.

The authors lay out 12 "facts' about the mortgage crisis. Their explanations of each of these are long and detailed. We have attempted to summarize them in just a few words. The entire paper is available here.

- Fact 1: Resets of adjustable rate mortgages did not cause the foreclosure crisis

The authors analyzed the rate increases experienced by certain types of adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs) and the defaults rates after these adjusted and found little correlation between the two. They found that among foreclosed borrowers with other types of "exotic" mortgages which also could result in payment shocks 84 percent were making the same payment when they defaulted as when they originated the loan and that 59 percent actually had fixed-rate loans.

- Fact 2: No mortgage was "designed to fail"

Some critics have argued that the very existence of some types of mortgages is evidence that borrowers were misled. Reduced documentation loans, loans with no downpayments or to borrowers with poor credit histories were not designed to fail; the large majority succeeded for borrower and lender alike.

- Fact 3: There was little innovation in mortgage markets in the 2000s.

There are two arguments here - first that lenders began to offer totally new types of mortgages or the more nuanced version that the market for nontraditional loans expanded. Instead history shows that the emergence of nontraditional mortgages predates the housing boom by many years. The payment option ARM, for example, was originated in 1980 and endorsed by the Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Home Loan Bank Board in 1981. However these loans were not highly visible as they were generally held in bank portfolios.

- Fact 4: Government policy toward the mortgage market did not change much from 1990 to 2005.

Again there are two arguments here - that there was too little government regulation of the mortgage markets and that government interventions went too far in an attempt to expand homeownership resulting in lenders abandoning prudent underwriting guidelines.

In fact, the authors say, while there was a lot of talk from government officials about lending and homeownership in the 1990s and early 2000s, actual market interventions were modest, especially as compared to what they call massive federal interventions in the immediate postwar era when over 50 percent of loans were government backed and average down payments on VA loans were 2 percent.

- Fact 5: The originate-to-distribute (OTD) model was not new.

The Dodd-Frank Act was motivated to a large extent by the OTD model and the need to keep lender's "skin in the game." Yet the authors maintain that the OTD model was central to the U.S. mortgage market for decades before the financial crisis. The model was originally adopted by mortgage companies but had spread to other financial institutions by the 1970s and by the late 1980s savings and loan institutions sold almost as many loans as they originated. The decline of the originate-to-hold model was well underway 30years before the boom of the 2000s.

- Fact 6: MBSs, CDOs, and other "complex financial products" had been widely used for decades.

The availability of these securities date back to the 1970s and even the most recent variety, convertible debt obligations had, through its merger with asset backed securities (ABS CDOs), reached maturity by the early 2000s. In short, the authors say, "the idea that the boom in securitization was some exogenous event that sparked the housing boom receives no support from the institutional history of the American mortgage market."

- Fact 7: Mortgage investors had lots of information

Contrary to the inside job theory, investors had plenty of information about the product they were buying. There were prospectuses with detailed information on the underlying loans in pools at origination and the information flow continued after the deals were sold to investors by way of monthly loan-level information on every loan in the pool. They also had tools that allowed them to use the data to price securities.

- Fact 8: Investors understood the risks.

Using the information and tools referenced above, investors were able to predict with a fair degree of accuracy how mortgages and securities would perform under various macroeconomic scenarios. Analysts such as Lehman brothers presented some gloomy forecasts of loan performance under scenarios of falling prices painting pictures of massive losses.

- Fact 9: Investors were optimistic about house prices.

Despite analyses such as that done by Lehman, investors and analysts actually gave little credibility to the most devastating of the predictions. The most optimistic of the price scenarios were also given the highest probability ratings. Even in 2006, after house prices had crested and begun to fall and well into 2007, the analysts were convinced that the decline would prove transitory and that prices would soon resume their upward march.

- Fact 10: Mortgage market insiders were the biggest losers

If the inside job theory is to prevail then it follows that insiders took advantage of outsiders and should have realized the greater gains while the outsiders lost. Instead, the authors contend that the opposite occurred.

There were the massive losses among the institutions that originated the loans. The top ten including Citibank, UBS, Merrill Lynch, and HSBC lost a combined total of $217.4 billion even before the collapse of Lehman Brothers. "Indeed, the large insider losses have led many researchers to question whether lenders actually even used the OTD model given the level of subprime mortgage risk they retained."

- Fact 11: Mortgage market outsiders were the biggest winners

When we turn to the winners the pattern is equally stark. The biggest beneficiary from the crisis was hedge fund manager John Paulson who, along with his assistant Paola Pellegrino, both total mortgage outsiders, bought billions of dollars of credit and attributed their success to a successful bet that house prices would decline. Another huge winner was a medical doctor who won because he was willing to read complex prospectuses carefully and pick the dodgiest loans to bet against.

The authors point out that the most useful demarcation to make when thinking about the mortgage market is not between insiders and outsiders but about those who thought house prices would continue to rise and those who were willing to bet they would fall. - Fact 12: Top-rated bonds backed by mortgages did not turn out to be "toxic." Top-rated bonds in CDOs did.

The ratings agencies have come in for enormous amounts of criticism about ways in which they rated subprime securities and accusations of conflicts of interest. The authors say the truth is more nuanced and the top-rated tranches of subprime securities fared better than many people realize.

Investors lost money on less than 10 percent of private-label AAA-rated securities because of credit protection which absorbed most of the losses. For subprime deals the principal balance of the non-AAA securities was often more than 20 percent. Given a 50 percent recovery rate on foreclosed loans, 20 percent credit protection means that 40 percent of the borrowers could suffer foreclosure before the AAA-rated investors suffered a single dollar of loss. However where investors suffered losses on less than 10 percent of the AAA-rated tranches from the original subprime securities, they suffered losses on all but 10 percent of AAA-rated ABS CDOs. The main failure of the rating agencies was not a flawed analysis of original subprime securities, but a flawed analysis of the CDOs composed of these securities.

The 12 facts consistently point to higher price expectations as a fundamental explanation for why credit expanded during the housing boom.

The insider/outsider theory results in a focus on what has come to be known as misaligned incentives and in the conventional narrative these incentives then led to the bubble. There is no doubt that the availability of credit expanded during the housing boom or that many borrowers received mortgages for which they never would have qualified before. The question is why the expansion took place and the facts simply suggest that the expansion occurred because people believed that housing prices would keep going up, the defining characteristic of an asset bubble. The authors argue that "neither the facts nor economic theory draw an obvious causal link from underwriting and financial innovation to bubbles."

The authors say they are sympathetic to the idea that securitization had some role in the financial crisis and there are also suggestions that some fundamental determinants of housing prices such as the monetary policies in the 2001 recession or higher savings rates in developing countries caused prices to begin to rise in the early 2000s and at some point the increases became self-perpetuating.

"Of course, the unanswered question is why this bubble occurred in the 2000s and not some other time. Unfortunately, the study of bubbles is too young to provide much guidance on this point. For now, we have no choice but to plead ignorance, and we believe that all honest economists should do the same. But acknowledging what we don't know should not blind us to what we do know: the bursting of a massive and unsustainable price bubble in the U.S. housing market caused the financial crisis."

It is important to keep inside/outside theory and the bubble theory separate as they suggest very different agendas for regulators and economists. If the inside story is true then prevention of a future crisis requires regulations that insure disclosure to borrowers and investors and that incentives are properly aligned. If the problem was a collective self-fulfilling mania, then such regulations will not work. For economists, the bubble theory implies that research should focus on a more general attempt to understand how beliefs are formed about the prices of long-lived assets. Through all the bubbles of history no robust theory has emerged to explain what happened. "Scientific ignorance about what causes asset bubbles implies that policymakers should focus on making the housing finance system as robust as possible to significant price volatility, rather than trying to correct potentially misaligned incentives."