Two New York Federal Reserve Bank economists are asking whether the tax reform act that went into effect at the beginning of 2018 is playing a role in the decline of home sales. Richard Peach and Casey McQuillan, writing in Liberty Street Economics, say that the broad-based slowing in housing market activity coincided with a roughly 70 basis point rise, from 3.9 percent to 4.6 percent, in the thirty-year fixed-rate mortgage. During the period in which rates were increasing, from the fourth quarter of 2017 to the third quarter of 2018, new home sales declined 7.6 percent and sales of existing homes dropped 4.6 percent.

The two point out, however, that those declines in sales were larger than in the two previous periods of significant rate increases. They theorize that provisions in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) are contributing to the downturn.

The authors reference a post in Liberty Street a year ago that took a detailed look at provisions of the TCJA that might affect the cost of homeownership. That analysis concluded that homeowners would experience significant increases in those costs, especially those living in areas with high income and property taxes. Deductions for state and local taxes, referred to as SALT deductions are capped at $10,000. Authors of the current article also took into consideration the lower ceiling on a mortgage balance ($750,000) for which interest can be deducted and how the lower marginal tax rates affect the value of those deductions.

Peach and McQuillan compared the 7.6 percent dip in home sales in the recent period of rising rates with those from Q2 2016 to Q1 2017 when rates rose about 60 basis points and home sales grew 10.3 and those from Q1 2013 through Q4 2013 when the increase was 80 basis points and home sales fell 1.0 percent.

In the most recent episode, the largest declines in sales tended to be in the highest price range, which is where homebuyers would be most affected by the tax changes mentioned before. To the extent that sales fell in previous periods, the declines were concentrated in the lower price ranges while the sales in higher price ranges continued to increase.

The authors say that the strength of the economy in 2018 and the strong pace of job creation indicates that the housing market should be able to shrug off the interest rate increases as they did in the two earlier periods. The difference this time would seem to be attributable to the tax code changes.

They developed a model which used the relationship between the costs of owning and renting to compute the user cost of capital for owner occupants who itemize deductions It is widely accepted, they say, that the user cost of capital strongly influences demand for owner occupied housing. They then compared changes in the user costs of capital in the three periods.

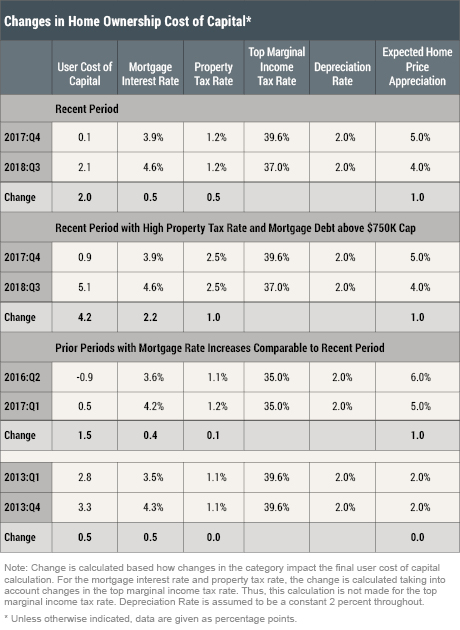

Their analysis took into account mortgage rates, median property taxes in the U.S., and depreciation. The latter is offset by capital gains from expected home price appreciation. These calculations bring the final user cost of capital for the quarter to essentially zero, or 0.1 percent. As shown in the table below, the calculation was replicated for each quarter with the appropriate housing costs variables.

The third quarter of 2018 was further analyzed with information on the changes in the tax treatment of homeownership. The top marginal income tax rate fell from 39.6 percent to 37 percent, meaning that the tax savings from itemized deductions fell by 2.6 percentage points. Property taxes are assumed to be at the national median of 1.2 percent of property values so that, at the margin, property taxes are no longer deductible although mortgage interest payments still are. The effect is to raise the effective property tax rate by 0.5 percentage point. From this they estimate that the user cost of capital to owners increases from 0.1 percent to 2.1 percent, and that a major part of this is due to a 1 percentage point decline in expected home price appreciation.

They also did an analysis for the

recent period focusing on high-priced homes in higher taxed areas. There they

assume property taxes at 2.5 percent of the home's value, typical for such

areas, and that the owner has borrowed more than the $750,000 cap, meaning the

mortgage interest is no longer deductible at the margin, raising the effective

mortgage rate by 2.2 percentage points. Under these assumptions, the cost of

capital appears to increase from around 1 percent to 5 percent for these

homes.

Of the three periods, the recent one experienced the greatest increase in user

cost of capital. From the second quarter of 2016 through the first quarter of

2017, the marginal user cost rose around 1.5 percentage points as the result of

higher mortgage rates, a slight increase in the median property tax rate, and

lower expectations for home price appreciation. In the first quarter of 2013

through the fourth quarter of 2013 episode, the marginal user cost rose by only

0.5 percentage points because of the increase of mortgage interest rates. Both

are less than in the 2017-2018 episode, particularly under the assumptions for

higher-priced homes in high-tax jurisdictions.

The authors concede that their findings are not conclusive, but they are

consistent with the view that the TCJA has contributed to the slowing of

housing market activity that occurred over the course of 2018. Specifically,

this slowdown stems from a higher user cost of capital caused by lower marginal

tax rates, the $10,000 cap on the deductibility of state and local taxes, and

the lower limit for the amount of mortgage debt on which interest payments are

deductible.