It can require as little as replacing doorknobs with levers or as complex as installing a walk-in shower, but Fannie Mae says very few existing homes are currently set up to allow their inhabitants to "age-in-place." The company takes an in-depth look at the issue in its February Insights, after its recent survey of the over age 55 population found that two thirds of older homeowners hope to do just that as do 44 percent of older renters.

The report, compiled by Freddie Mac Chief Economist Sean Becketti and Elias Yannopoulos, a quantitative analyst in the company's Economic and Housing Research Group, notes that while the desire to remain in an existing home is high (and increases with age), many residences make aging in place a challenge. Stairs, doorways and halls too narrow to accommodate wheelchairs, inadequate lighting and other issues can all be problems for people as they age. Two-thirds of respondents to Freddie Mac's survey said their own homes lack accessiblity for someone with arthritis, limited mobility, or in a wheelchair.

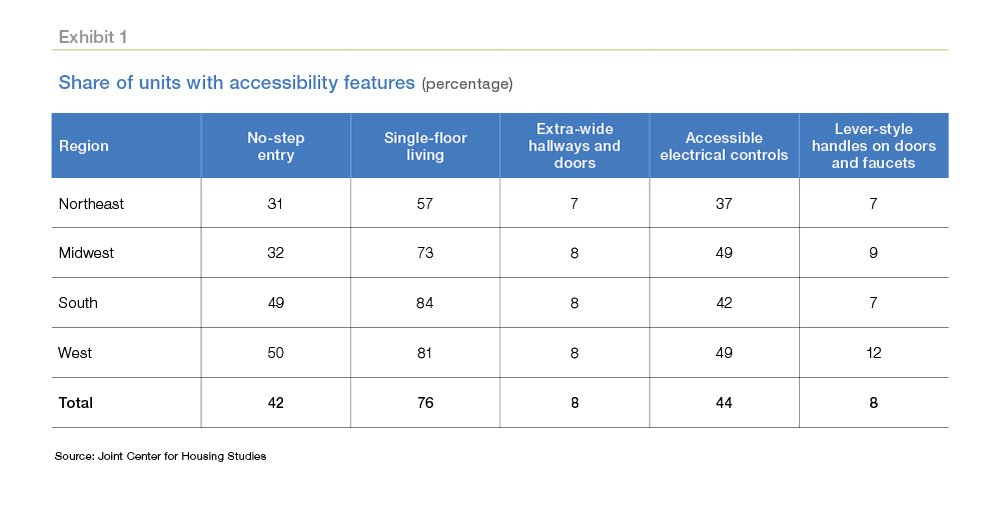

The report quotes the Joint Center for Housing Studies' list of five essentials a home needs to allow its use by persons with age-related restrictions or disabilities:

- No-step entries to the main floor of the house.

- Single-floor living. A bedroom and full bathroom on the main floor of the house.

- Extra-wide hallways and doors. Wheelchairs require a minimum of 36 inches for doors and halls. Standard doorways are only 28 to 32 inches wide.

- Accessible electrical controls. Controls that can be reached from a wheelchair.

- Lever-style handles on doors and faucets.

Many of the survey respondents who said their homes would require retrofitting to allow them to remain living there also expressed confusion and concern about their ability to pay for these renovations.

According JCHS, there are more seniors in need of retrofitting than there are homes that include their essential features for aging in place. The Center estimates that only one percent of the current housing stock-a little over one million units-offers all five of the accessible features listed above, and fewer than four percent of single-family houses offer the three that are most critical, single-floor living, extra-wide hallways and doors, and no-step entrances. These shortages are also affected by regional differences.

The types of housing that are common in the various regions are linked to both the existence of essential features as well as the ease of retrofitting. Two story central hall colonials and capes are popular in the Northeast, and Midwest and JCHS estimates single-floor living is possible in only 57 percent and 73 percent respectively of the homes in the two regions. Ranch-style homes West and Southwest can be easier to adapt; over 80 percent can accommodate single-floor living. The average age of the housing stock in the West and South is also lower than the average age of the stock in the Northeast, and newer homes can be easier to retrofit.

The five essential features listed by JCHS make it possible for persons with limitations to stay in their home, but it might not always make it life easy or comfortable. An alternative approach is universal design, where buildings, products, and environments are designed to be inherently accessible to older people, children, and people both with and without disabilities, that is, everyone. Freddie Mac points to curb cuts, and sidewalk ramps as examples; used by all, but essential for those in wheelchairs. In addition to step-free entrances, one floor living, and wide hall and doorways, the other features of universal design are:

- Lever door and faucet handles

- D-shaped cabinet and drawer handles

- Multi-height kitchen countertops that can be used while standing or seated

- Kitchen and bathroom cabinets and shelves that are easy to reach

- A bathtub or shower with a non- slip bottom or floor, and preferably with zero entry

- Blocking in the bathroom walls so grab bars can be added as needed

- Well-lit hallways and stairways

- Secure handrails on both sides of stairways

- Easy-open windows

Universal design is more easily applied in new construction but some elements can be retrofitted into existing facilities. Often however, this is at the expense of aesthetics; it can be difficult to avoid an ugly retrofit.

Freddie Mae sees the need and desire for retrofitting and the impact of doing it as enormous. The over 55 population comprises over a quarter of the U.S. population, about 90 million people, and will continue to grow, reaching 136 million by 2050. Currently 69 million of those over 55 are homeowners and 43 million of them want to age in place. Of that population, 35 percent indicate their homes are already suitable. Fifty-seven percent of that group want to age-in-place.

The older the respondent, the more likely they are to desire aging in place - more than twice those over 75 than those 55 to 64. This suggests the two-thirds number may underestimate those who may eventually want to age-in-place. Lower-income households are more likely to want to do this, however, these households may find the cost of retrofitting challenging.

The survey also pointed to an unexpected link between marital status and desire to age in place with the windowed and never married most likely to want to stay put, even though the hurdles are greater for those who live alone. The report speculates that widowed respondents may wish to stay near family and friends while never-married individuals may simply be more self-reliant.

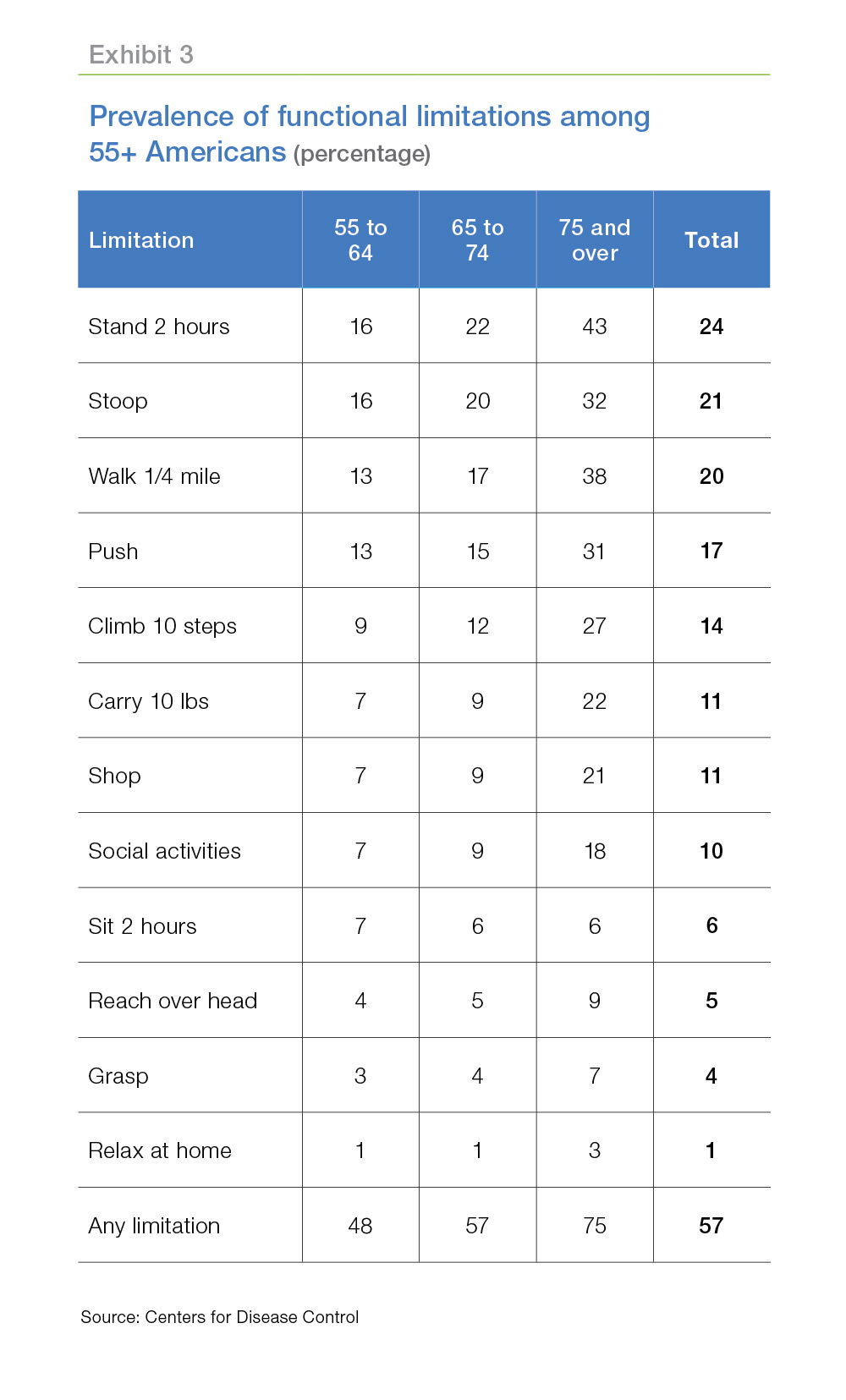

The need for retrofitting rises with age as physical limitations grow. Over half of all 55+ Americans are impacted by at least one physical limitation as are three-quarters of those over 75.

Homeowners and renters face different challenges for aging in place. Homeowners on average have higher income than renters, potentially allowing them to pay for retrofitting. Renters are more mobile and instead of retrofitting, can simply relocate to a more suitable apartment; many newer ones are more accessible than older, single-family homes. Marital status also plays a role; the presence of a partner can help to compensate for some functional deficits. Two-thirds of 55+ homeowners are married, but only a third of renters are.

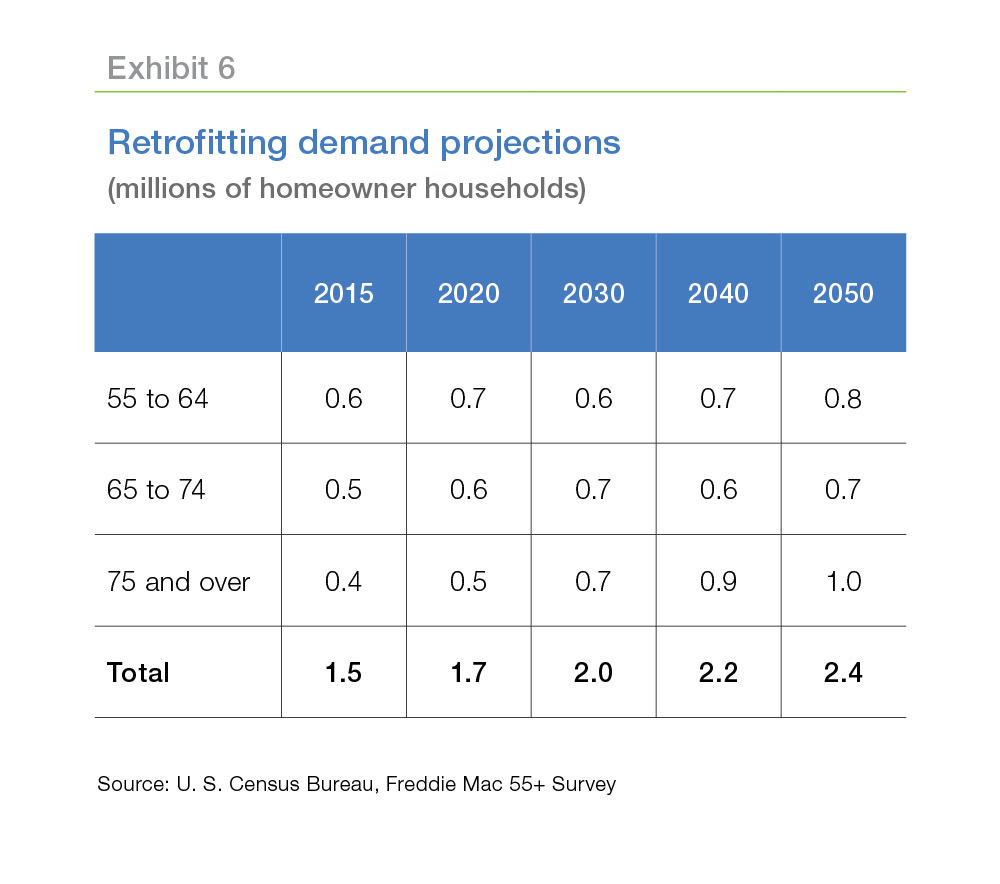

Exhibit 6 displays a rough estimate of the current and future annual demand for retrofitting, measured by the number of homeowner households likely to undertake at least some type of retrofitting. This suggests the stock of aging-in-place-ready properties may increase significantly. For instance, if just 10 percent of these households install all five JCHS essential features, the number of units with all five features will double in under 10 years.

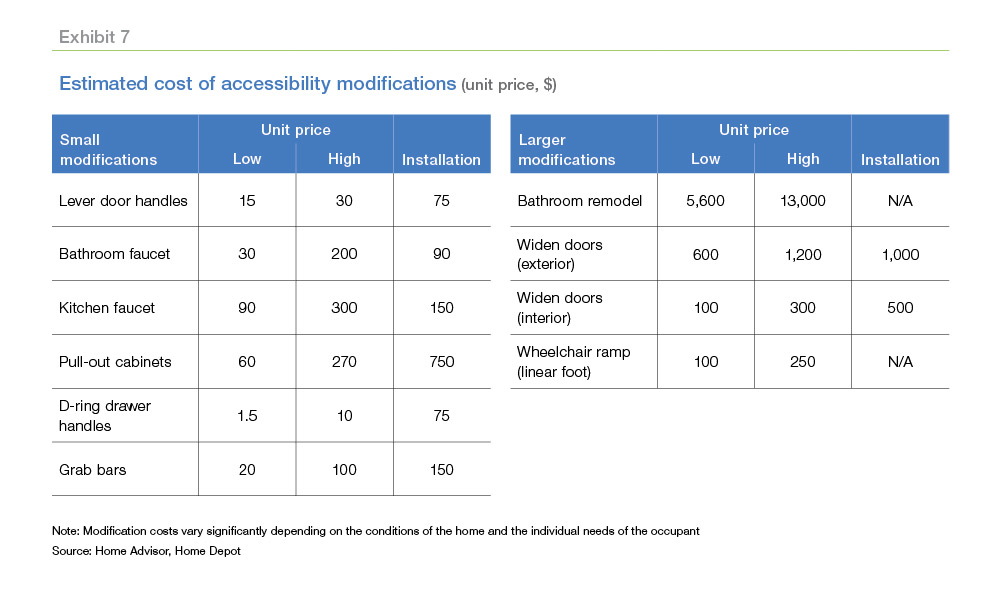

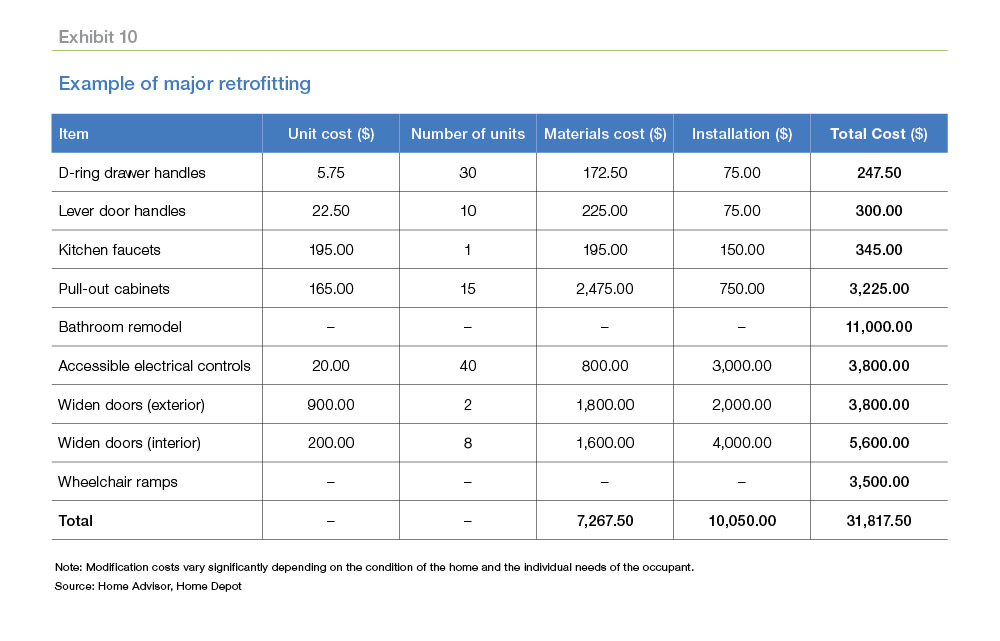

The extent of needed retrofitting and the cost can vary considerably, depending on the type and condition of the home and the physical limitations of the homeowner. Some installations can be DIY, saving money, however delaying too long may make installation a physical impossibility. Exhibit 7 shows prices of some common retrofit features.

Homeowners may need to decide between a massive retrofit which would allow them to stay through major age related restrictions - such as confinement to a wheelchair - or only minor changes which would add to the houses safety and convenience but would require relocation if physical limitations increase. A handy homeowner might be able to make minor changes - lever on doors, grab bars - to make a home livable for years for under $1,000. A complete retrofit could cost 30 or 40 times more than that.

Of course, there is always an economic side to a story and Becketti and Yannopoulos say the growth in the 55+ population combined with the strong desire to age in place should provide a boost to the building material and construction sectors.

Using an estimated retrofitting expense of $2,700 per 55+ household, (data from the 2013 American Housing Survey) retrofitting that was estimated at $4 billion in 2015 (around 5 percent of expenditures on all repairs and additions by over 55 households) is expected to grow to $6.1 billion by $2050.

Freddie Mac puts some caveats on these estimates. Americans may remain healthier in the future, continuing to live into their 80s and 90s in homes that are now viewed as unsuitable and delaying the need for adaptations. Americans may also overestimate their commitment to aging in place or may change their minds when they discover how difficult or possibly unaffordable, retrofitting will be.

A larger share of new homes may adopt universal design principles which will eliminate the need for some, but not all, retrofitting. Also, both the housing industry and organizations focusing on older Americans have begun to respond to the demand for retrofitting with guides for homeowners and certifications to help professionals understand and respond to that demand.

The authors also point out that aging in place can require more than physical changes to the home. Cleaning and maintenance may become more difficult over time and physical limitations may pose more challenges outside the home; particularly with transportation. Some hurdles can be surmounted with sufficient income; hiring help with cleaning, landscaping, and maintenance or booking taxis or other forms of transport. Money however, cannot overcome cognitive deterioration. As time passes, seniors may need assistance dealing with finances and medical needs and these may be compounded by the isolation suffered by many without nearby families and with narrowing circles of friends.