The library of articles citing the alarming lack of new construction continues to grow. Freddie Mac, the Urban Institute (UI), and John McManus of Builder Pulse magazine have all written articles about what some of them called a crisis for the housing industry. UI put the shortfall between supply and demand in 2017 at 350,000 units. Freddie Mac's economists estimated that the long-term deficit could be 2.5 to 4.0 million units each year. McManus went to far as to say housing may be broken because of the dislocation created by too few houses. Now the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) has produced a study about some of the ramifications.

Paul Emrath focuses on one of them in an article in NAHB's Eye on Housing blog. He points out that, since 2006, builders have failed to match the average of 1.5 million homes built each year from 1961 through 2000. The number of homes completed has been below the number of net new household formations. One outcome of this shortfall has been that homes tend to remain in nations housing stock and inhabited for longer periods. Because of this he says, attempts to upgrade housing through new development standards or building codes do not make a lot of sense.

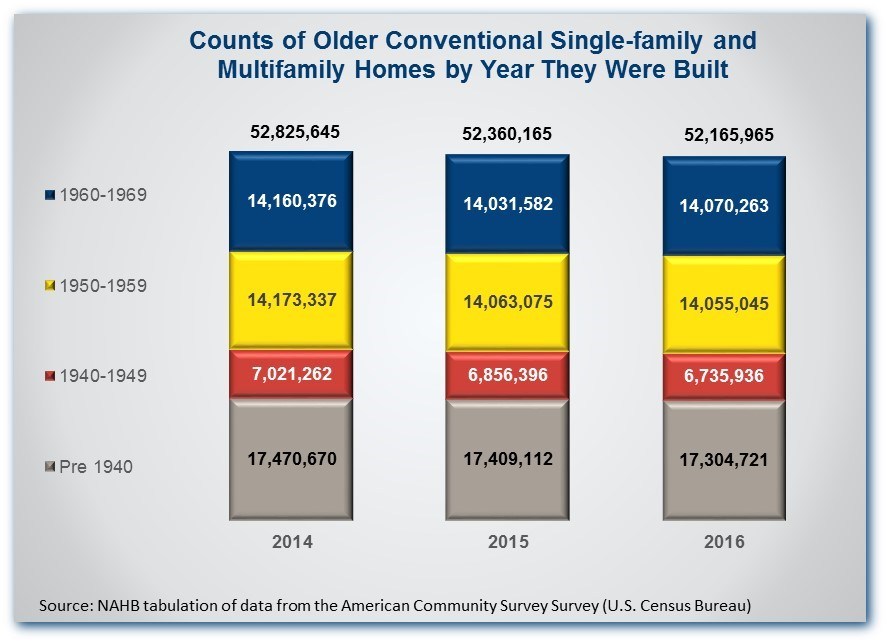

The Census Bureau's American Community Survey (ACS) shows that the number of homes built prior to 1970 has been declining slowly; there were 52.83 million of them in 2014, and 52.17 million in 2016. This means that only about six of every 1,000 homes built before 1970 are removed from the housing stock each year, and the Census Bureau indicates it may be even fewer. Their models show that the number could be less that one per 1,000 in the Northeast and West regions.

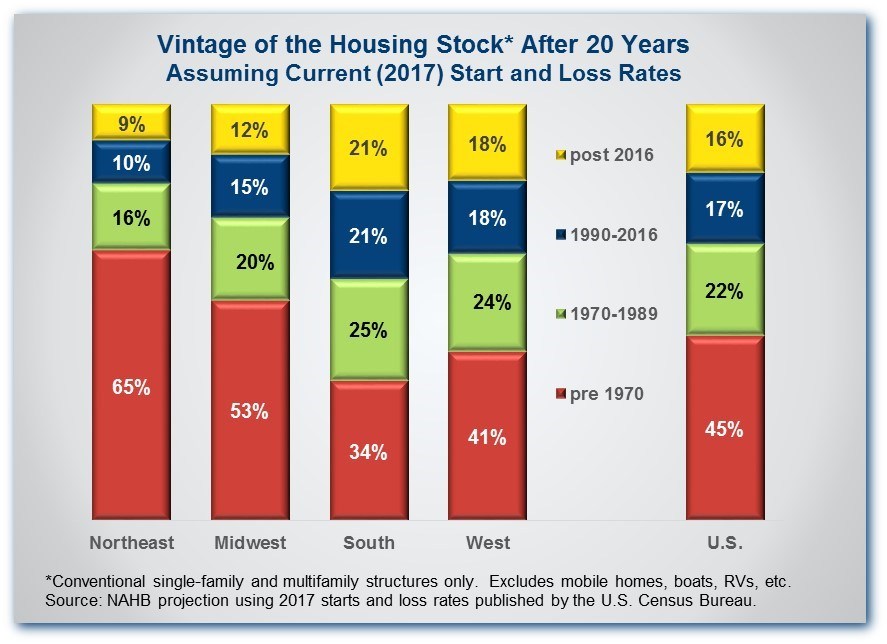

Emrath says loss rates as small as these are not sustainable; the lower of the Census estimates would imply that half of new homes built in some regions last 1,000 years. He suggests imagining that this rate of removal remains and that 1.20 million new homes are built every year (there were 1.20 million housing starts and 1.15 million completions in 2017, the highest either number has been in a decade.) After 20 years, only 16 percent of the nation's housing stock would consist of homes that were one to 20 years old while 45 percent would have been built before 1970, 65 percent in the Northeast.

Older homes can be charming and some homeowners are able to keep them updated and in good repair, but Emrath reminds that before 1970 there were no codes or standards for energy efficiency. Neither did construction have to meet the resiliency requirements motivated by Hurricane Andrew in 1992 nor the Northridge earthquake in 1994. Many code changes targeting fire safety (such as requirements for smoke alarms, fire separation, fire blocking, draft stopping, emergency escape openings, electrical circuit breakers, and capacity and outlet separation) were also implemented after 1970.

In short, Emrath concludes, "In just about every way imaginable, new homes are being built to higher standards than they were in 1970. So, if you want to improve the built environment, one of the first things you need to do is figure out simply how to increase the production of new homes, built to modern standards, so it becomes possible to retire more of the older ones."