While housing starts have picked up in recent months, the lack of new construction has been called a crisis by Freddie Mac, state and federal policymakers, and consumer groups, adding as it has to an overall shortage of housing for both sale and rent. Urban Institute (UI) analyst John Walsh recently wrote in UI's Urban Wire blog that one problem with 21st Century homebuilding is that it still employs 20th Century processes. These methods, that entail building largely on-site, make construction less efficient, exacerbate labor and weather issues, and are costlier than building off-site.

Walsh quotes information gathered at a recent UI symposium "Reimagining Housing; Closing the Equity and Supply Gaps" which examined the benefits of and challenges to an increased use of off-site construction. He quotes one participant, Gerry McCaughey, CEO of the off-site construction company Entekra, as likening what his company and industry do to buying a car. "You wouldn't want a car dealership to ship your new car in parts to your driveway and have workers come by your house for weeks to put it together."

Off-site construction uses industrial-size machines that can mass produce home parts, reducing the need for labor, one of the concerns home builders have been dealing with since the Great Recession. Even with sufficient labor, on-site construction has relatively lower productivity than other industries.

How do the costs off-site construction compare to "traditional building?" McCaughey, whose company builds prefabricated or "kit homes," says the process increases productivity three-fold. The Manufactured Housing Institute puts the price to build a manufactured home at about $50 a square foot versus $111 for stick building.

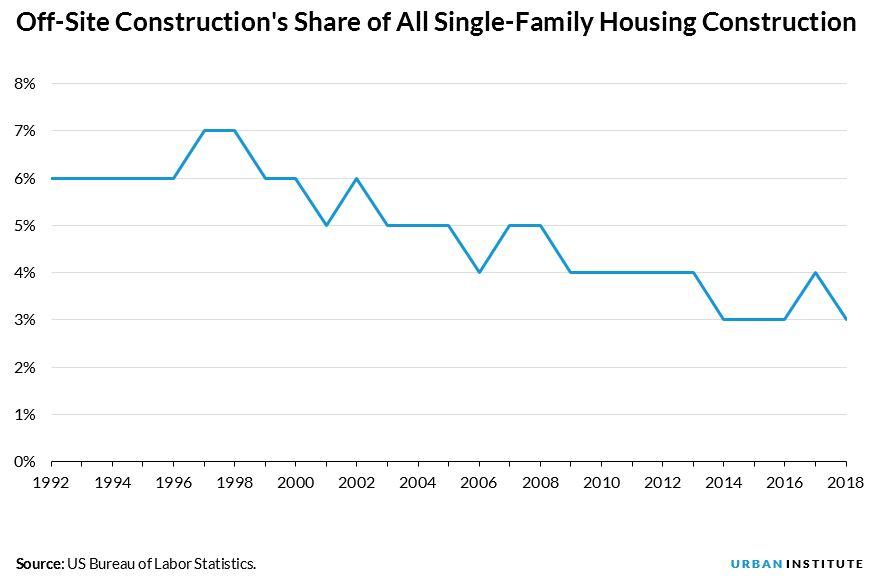

It's not like off-site building is an unproven technology. Ninety percent of homes in Sweden are built off-site, but in the U.S. the attempts to employ those practices have been sporadic. Sears and other companies sold as many as 250,000 "kits" before and after World War II, but the practice hit a quarter-century low in 2018. Manufactured housing (frequently called mobile homes although few actually are portable once on-site) made up about half of all new single-family production in the 1960s and 1970s but only around 10 percent today.

The symposium participants identified three barriers to that are holding back wider adoption of off-site building in today's market. The up-front costs can be prohibitive. Significant capital is needed to build and equip the production facilities and these investments become less profitable in the later stages of the business cycles. Because on-site builders are buying materials and subcontracting for labor on virtually a house-by-house basis they can quickly adapt to downturns in demand.

Walsh says diversification could help with this issue. Where factories can expand their products beyond single-family units to commercial or multifamily construction, they can hedge against downturns in any single market segment.

Consumer preference is another issue. Buyers continue to show a strong preference for homes built on site, especially as compared to manufactured houses. Those properties, which are almost entirely factory built and trucked to the site for final assembly, have been stigmatized for being cheaply built. The mass-produced aspect also runs against consumer desires for design flexibility.

Producers of manufactured housing have been incorporating more varied designs such as homes with porches or pitched roofs to appeal to buyers. They also find more demand for their product among communities that have not had ready access to homeownership.

Both local codes and mortgage financing have worked against broader acceptance of manufactured housing. Local zoning often explicitly bans manufactured homes as do some subdivision covenants. Building codes are a real challenge as there may be multiple jurisdictions with differing codes within a single manufacturer's market area

Chattel loans (i.e. auto loans) dominate financing for manufactured housing. These are more costly than mortgages and finance only the structure but not the underlying land. This also tends to work against building equity in the home. Walsh says the reliance on chattel loans arise out of confusion - buyers don't understand the title issues involved - and because chattel lenders are usually what is available at manufacturers sale sites.

Some of these institutional problems are being addressed. The Department of Housing and Urban Development has a manufactured housing code which preempts local building codes and could be adapted to other types of off-site building. Fannie Mae is helping with the financing issue. Its MH Advantage program provides an accessible alternative financing mechanism to the chattel loan as part of their "duty to serve" commitment.